Chapter 7: How to Set Up Networking

Networking is what needed to:

- connect 👉 services need to communicate over the network

- secure 👉 environment need to be isolated from each other (so they can’t talk to each other)

your applications.

This chapter will walkthrough the concepts and examples:

| Concept | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Public networking | Expose your apps to the public internet via | |

| - public IPs | - Deploy servers with public IPs in AWS | |

| - domain names | - Register a domain name for them in Route 53 | |

| Private networking | Run apps in private network to | - Create a Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) in AWS |

| - protect them from public internet access | - Deploy servers into VPC | |

| Network access | Securely access private networks | Connect to a server in a VPC in AWS using |

| - using SSH, RDP, VPN | - SSH and a bastion host | |

| Service communication | Connect & secure communicate between apps | Use Istio as a service mesh |

| - in a (micro)services architecture | - for microservices running in Kubernetes |

Public Networking

Almost everything you’ve deployed so far has been accessible directly over the public internet.

e.g.

- An EC2 instance with a public IP address like

3.22.99.215 - A load balancer with a domain name like

sample-app-tofu-656918683.us-east-2.elb.amazonaws.com

Public IP Addresses

IP : Internet Protocol : a protocol (set of rules) for : - routing : - addressing : … data across networks

tip

There are 2 major versions of IP: IPv4 & IPv6.

- IPv4: First major version, around since 1980s, is the dominant protocol of the internet.

- IPv6: The successor version, introduced in 2006, is gradually graining adoption

IP Address (IPv4 address)

: 👕 unique identifier used to determine who is who on the Internet

: 👔 a numerical label such as 192.0.2.1 that is assigned to a device connected to a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication

: IP addresses serve two main functions:

: - network interface identification 👈 Which host is it?

: - location addressing 👈 Where is the host?

An IPv4 addresses

- is fixed length of four octets (32 bits)1 👈 There are $2^{32}$ IPv4 addresses.

- begins with a network number,

- followed by local address (called the “rest” field).

note

Running out of IPv4 addresses is one of the reason

- the world is moving to IPv6, which

- uses 128-bit addresses that are typically displayed as

- eight groups of four hexadecimal digits2, such as

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334.

- eight groups of four hexadecimal digits2, such as

- uses 128-bit addresses that are typically displayed as

Though, IPv6 adoption is still under 50%, because millions of old networking devices still don’t support IPv6.

Represent of an IPv4 address:

IPv4 Example Decimal value of the IPv4 address In dot-octal notation o.o.o.o(4 octets)$013_{8}.014_{8}.015_{8}.016_{8}$3 👇4 In binary notation xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx(32 bits)$00001011 00001100 00001101 00001110_{2}$ $185 339 150_{10}$ In dot-decimal notation Y.Y.Y.Y$11_{10}.12_{10}.13_{10}.14_{10}$ 👆5

note

If your computer is connected to the internet, to communicate with another computer (on public internet), you only need that computer’s IP address.

How to having your computer “connect to the internet”?

Your computer needs to have a valid IP address (in your network):

In other words, your computer need to know:

- where it is 👈 Which network (of type A, B, C) or subnet6?

- what its ID is 👈 Which host it is?

There are 2 main methods for allocating the IP addresses:

-

Classful networking address: 👈 The network prefix has fixed-length (7, 14, 21 bits)

There are 3 main classes of internet addresses:

- In class a, the high order bit is zero, the next 7 bits are the network, and the last 24 bits are the local address;

- In class b, the high order two bits are one-zero, the next 14 bits are the network and the last 16 bits are the local address;

- In class c, the high order three bits are one-one-zero, the next 21 bits are the network and the last 8 bits are the local address.

-

Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR): 👈 The network prefix has variable length

[!TIP] CIDR grants finer control of the sizes of subnets allocated to organizations, hence slowing the exhaustion of IPv4 addresses from allocating larger subnets than needed.

Represent of an IP address:

-

in bit array7 (in binary number)

x: indicates a bit. n: indicates a bit used for the network number (aka network ID). H: indicates a bit used for the local address (aka host ID).0xxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx (Class A) 0nnnnnnn HHHHHHHH HHHHHHHH HHHHHHHH <-----> <------------------------> 7 bits 24 bits Network add. Local address10xxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx (Class B) 10nnnnnn nnnnnnnn HHHHHHHH HHHHHHHH <-------------> <---------------> 14 bits 16 bits Network address Local address110xxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx (Class C) 110nnnnn nnnnnnnn nnnnnnnn HHHHHHHH <---------------------> <------> 21 bits 8 bits Network address Local address -

in decimal notation (in decimal number)

In bit array In decimal-dot notation Leading bits Network’s

bit fieldLeadings bits & network bits Address ranges of networks Address ranges of each network Address ranges of whole class Class A 07 bits

($2^7$ networks)0nnn nnnn👉 From 00.0.00.0.0.0to 127255.255.255127.255.255.255Class B 1014 bits

($2^{14}$ networks)10nn nnnn nnnn nnnn👉 From 128.00.0128.0.0.0to 191.255255.255191.255.255.255Class C 11021 bits

($2^{21}$ networks)110n nnnn nnnn nnnn nnnn nnnn👉 From 192.0.00192.0.0.0to 223.255.255255223.255.255.255

tip

There are a lot of names, don’t be confused:

Network addressis akanetwork ID,routing prefixLocal addressis akarest field,host identifier

For more information about IP Address, see:

All the public IP addressed are owned by IANA, which assigns them in hierarchical manner:

-

Top-level: IANA delegates blocks of IP addresses to Internet registries (that cover regions of the worlds)

-

These Internet registries, in turn, delegate blocks of IP addresses to network operators8, such as

- Internet Service Provider (ISPs)

- cloud providers, e.g. AWS, Azure, GCP

- enterprise companies…

-

Finally, these network operators assign IP addresses to specific devices.

e.g.

-

important

Key takeaway #1 You get public IP addresses from network operators such as cloud providers and ISPs.

For more information, see:

- What is the Internet Protocol (IP)? | CloudFlare Learning Center

- What is my IP address? | CloudFlare Learning Center

For even more information, see:

Domain Name System (DNS)

note

Before DNS, TCP/IP has another name system - the simple host table name system.

tip

An example host table on Linux - the file /etc/hosts - looks like this

# Loopback entries; do not change.

# For historical reasons, localhost precedes localhost.localdomain:

127.0.0.1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost4 localhost4.localdomain4

::1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost6 localhost6.localdomain6

# See hosts(5) for proper format and other examples:

# 192.168.1.10 foo.mydomain.org foo

# 192.168.1.13 bar.mydomain.org bar

name system : technology that allow computers on a network to be given both : - a conventional numeric address : - a more “user-friendly” human-readable name

domain name

: 👕 a unique, easy-to-remember address used to access websites, such as google.com (instead of a IP address 142.251.10.100)

Domain Name System (DNS) : new, current name system of the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP)

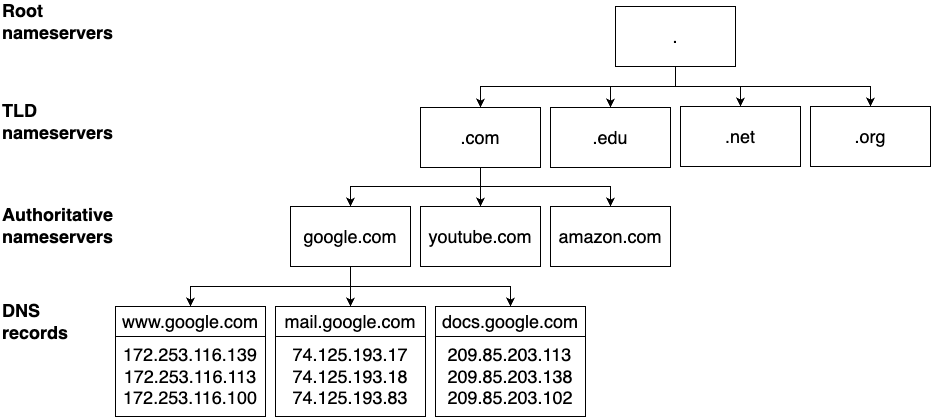

How DNS works

-

DNS stores

- the mapping from names to IP addresses

- in a globally-distributed hierarchy of nameservers

- the mapping from names to IP addresses

-

When you enter

www.google.cominto your web browser,-

your computer doesn’t talk directly to the nameservers

- instead it send sends a request to a local DNS resolver11.

-

-

The DNS resolver takes the domain name processes the parts in reverse order by making a series of queries to the hierarchy name servers

-

The DNS resolver’s first query goes to the root nameservers12 13:

The root nameservers return

- the IP addresses of the top-level domain (TLD) nameservers for the TLD you requested (

.com).

- the IP addresses of the top-level domain (TLD) nameservers for the TLD you requested (

-

The DNS resolver’s second query goes to the TLD nameservers14.

The TLD nameservers return

- the IP addresses of the authoritative nameservers for the domain you requested (

google.com).

- the IP addresses of the authoritative nameservers for the domain you requested (

-

Finally, the DNS resolver’s third query goes to these authoritative nameservers15

The authoritative nameservers return

- the DNS records that contain the information that is associated with the domain name you requested (

www.google.com)

- the DNS records that contain the information that is associated with the domain name you requested (

-

note

It takes 3 queries to get some DNS records of a domain name. Isn’t it too many round-trips?

- DNS is pretty fast

- There is a lot of caching that will reduce the number of look ups e.g. browser, OS, DNS resolvers, …

DNS records

DNS record : contains the information that is associated a domain name

There are many types of DNS records, each stores different kinds of information, such as:

- DNS

Arecord: stores the IPv4 address - DNS

AAAArecord: stores the IPv6 address - DNS

CNAMErecord: “canonical name” record thats stores alias for domain name. - DNS

TXTrecord: stores arbitrary text

When your browser looks up www.google.com, it typically requests A or AAAA records.

important

Key takeaway #2 DNS allows you to access web services via memorable, human-friendly, consistent names.

DNS Registration

-

The domain names are also owned and managed by IANA, who delegates the management to

- accredited registrars,

- who are allowed to “sell” domain names to end users

- are often (but not always) the same companies that run authoritative name services.

- accredited registrars,

-

After you lease a domain name, you have the permission to

- configure the DNS records for that domain

- in its authoritative name servers.

- configure the DNS records for that domain

-

Only after that, users all over the world can access your servers via that domain name.

note

Technically, you never own a domain name, you can only pay an annual fee to lease it.

Example: Register and Configure a Domain Name in Amazon Route 53

In this example, you’ll:

- Deploy a web app 👈 A simple HTTP server on several EC2 instances

- Set up a domain name (for it) 👈 Using Amazon Route 53 as the domain name registrar.

Register a domain name

Registering domain involves manual steps:

- Open Route 53 dashboard > Choose

Register a domain> ClickGet started - In the next page:

- In the

Search for domainsection > Use the search box to find an available domain - Click

Selectto add the domain to your cart. - Scroll to the bottom > Click

Proceed to checkout.

- In the

- In the next page:

- Fill out other details: How long? Registration auto-renew?

- Click

Next

- In the next page:

- Fill out contact details16

- [Optional] Enable privacy protection

- Click

Next

- Review the order in the summary page, then click

Submit - Open your email to confirm that you own the email address.

- Check your domain in registered domains page

- [For this example] Open the hosted zones page and copy the hosted zone ID.

tip

You can monitor the your registration process on the registration requests page

note

When you register a domain in Route 53, it automatically

- configures its own servers as the authoritative nameservers for that domain.

- creates Route 53 hosted zone for the domain

warning

Watch out for snakes: Registering domain names is not part of the AWS free tier!

The pricing varies based on the TLD:

- Domain with

.comTLD cost $14 per year (in September 2024)

Deploy EC2 instances

This example will

- use the

ec2-instances17 OpenTofu module, which is available at the sample code repo atch7/tofu/modules/ec2-instances - to deploy 3 EC2 instances

-

The OpenTofu root module

ec2-dns-

main.tf# examples/ch7/tofu/live/ec2-dns/main.tf provider "aws" { region = "us-east-2" } module "instances" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch7/tofu/modules/ec2-instances" name = "ec2-dns-example" num_instances = 3 # (1) instance_type = "t2.micro" ami_id = "ami-0900fe555666598a2" # (2) http_port = 80 # (3) user_data = file("${path.module}/user-data.sh") # (4) }- (1): Deploy 3 EC2 instances

- (2): Use the Amazon Linux AMI

- (3): Expose the port 80 for HTTP requests

- (4): Run the

user-data.shscript

-

Copy the user data script from chapter 2:

cd examples copy ch2/bash/user-data.sh ch7/tofu/live/ec2-dns/

[!WARNING] Watch out for snakes: a step backwards in terms of orchestration and security

This example has all the problems in Chapter 1 | Example Deploying An App Using AWS

-

Output the public IP addresses of the EC2 instances

output "instance_ips" { description = "The IPs of the EC2 instances" value = module.instances.public_ips }

-

-

Deploy the

ec2-dnsmoduletofu init tofu apply -

Verify the the app is deployed on these EC2 instance

curl http:<EC2_INSTANCE_IP_ADDRESS>

Configure DNS records

In this example, you’ll point your domain name at the EC2 instances (deployed in previous section)

-

Add the configuration for a DNS A record to the

ec2-dnsmodule# examples/ch7/tofu/live/ec2-dns/main.tf provider "aws" { # ... } module "instances" { # ... } resource "aws_route53_record" "www" { # TODO: fill in your own hosted zone ID! zone_id = "Z0701806REYTQ0GZ0JCF" # (1) # TODO: fill in your own domain name! type = "A" # (2) name = "www.fundamentals-of-devops-example.com" # (3) records = module.instances.public_ips # (4) ttl = 300 # (5) }The DNS record

- (1): … created in this hosted zone

- (2): … of type A

- (3): … for the sub-domain

www.<YOUR_DOMAIN> - (4): … point to the IPv4 addresses (of the EC2 instances you deployed)

- (5): … with the time to live (TTL)18 of 300 seconds.

For more information, see

aws_route53_recordOpenTofu resource’s docs -

Add output variable for the domain name

# examples/ch7/tofu/live/ec2-dns/outputs.tf output "domain_name" { description = "The domain name for the EC2 instances" value = aws_route53_record.www.name }

-

Re-apply the

ec2-dnsmoduletofu apply -

Verify the domain name works

curl http://www.<YOUR_DOMAIN>

Get your hands dirty: Managing domain names

-

Instead of several individual EC2 instances,

- use one of the orchestration approaches from Part 3,

- such as an ASG with an ALB

- figure out how to configure DNS records for that approach.

- use one of the orchestration approaches from Part 3,

-

Figure out how to automatically redirect requests for your root domain name (sometimes called the apex domain or bare domain) to your

www.sub-domain:e.g. redirect

fundamentals-of-devops-example.comtowww.fundametals-of-devsop.com.This is a good security practice because of how browsers handle cookies for root domains.

-

DNSSEC (DNS Security Extensions) is a protocol you can use to protect your domain from forged or manipulated DNS data.

- You may have noticed that in the Details section for your domain in your Route53 hosted zone page, it said that the

DNSSSEC statuswasnot configured. - Fix this issue by following the Route 53 DNSSEC documentation.

- You may have noticed that in the Details section for your domain in your Route53 hosted zone page, it said that the

Private Networking

private network : a network set up by an organization solely for that organization’s use : e.g. : - a home network : - an office network : - an university network : - a data center network : is locked down so only authorized individuals (from within that organization) can access it

Private Network’s Advantages

Defense in depth

defense-in-depth strategy : establish multiple layers of security : - providing redundancy in case there is a vulnerability in one of the layers

You should build your software in a similar manner with building a castle - using defense-in-depth strategy - establish multiple defense layers, if one of them fails, the others are there to keep you safe.

e.g. The servers (EC2 instances) deploy so far:

- has one layer of security - the firewall (security group) that block access to all ports by default

- one mistakes and these servers might become vulnerable, e.g. Someone will misconfigure the firewall and leave a port open, which be scanned all the time by malicious actors.

note

Many incidents are not the result of a brilliant algorithmic code cracking, but of opportunists jumping on easy vulnerabilities due to someone making a mistake.

warning

If one person making a mistake is all it takes to cause a security incident, then

- the fault isn’t with that person

- but with the way you’ve set up your security posture.

By putting your servers in a private networks, you have at least 2 layers of protections:

- First, a malicious actor have to get into your private network.

- Second, the actor have to find a vulnerability in your server.

tip

A good private network can create many more layers of security.

important

Key takeaway #3 Use a defense-in-depth strategy to ensure you’re never one mistake away from a disaster.

Isolate workloads

Separate private networks is one of the way to setup isolated environment.

e.g.

- Deploy different products, teams in separate private networks.

- Deploy data store servers and application servers in separate private networks.

If the workloads in separate private networks needs to communicate, you only allow traffic between specific IPs and ports.

tip

The other ways to setup isolated environments: different servers, different accounts, different data centers…

Better control and monitoring

Private networks give you fine-grained control over routing of:

- north-south traffic: traffic between your servers and the outside worlds

- east-west traffic: traffic between servers within your network.

This allows you to:

- add better security control

- setup monitoring

You should

-

almost always have all servers in a private network

-

only expose some highly-locked down servers, e.g. load balancers e.g. Capture flow logs that show all traffic going through your private network

-

manage traffic patterns

e.g. Shift traffic around as part of deployment or experiment

important

Key takeaway #4 Deploy all your servers into private networks by default, exposing only a handful of locked-down servers directly to the public Internet.

Physical Private Networks

note

Lossy compression Networking is a huge topic, what you’re seeing here is a highly simplified picture.

-

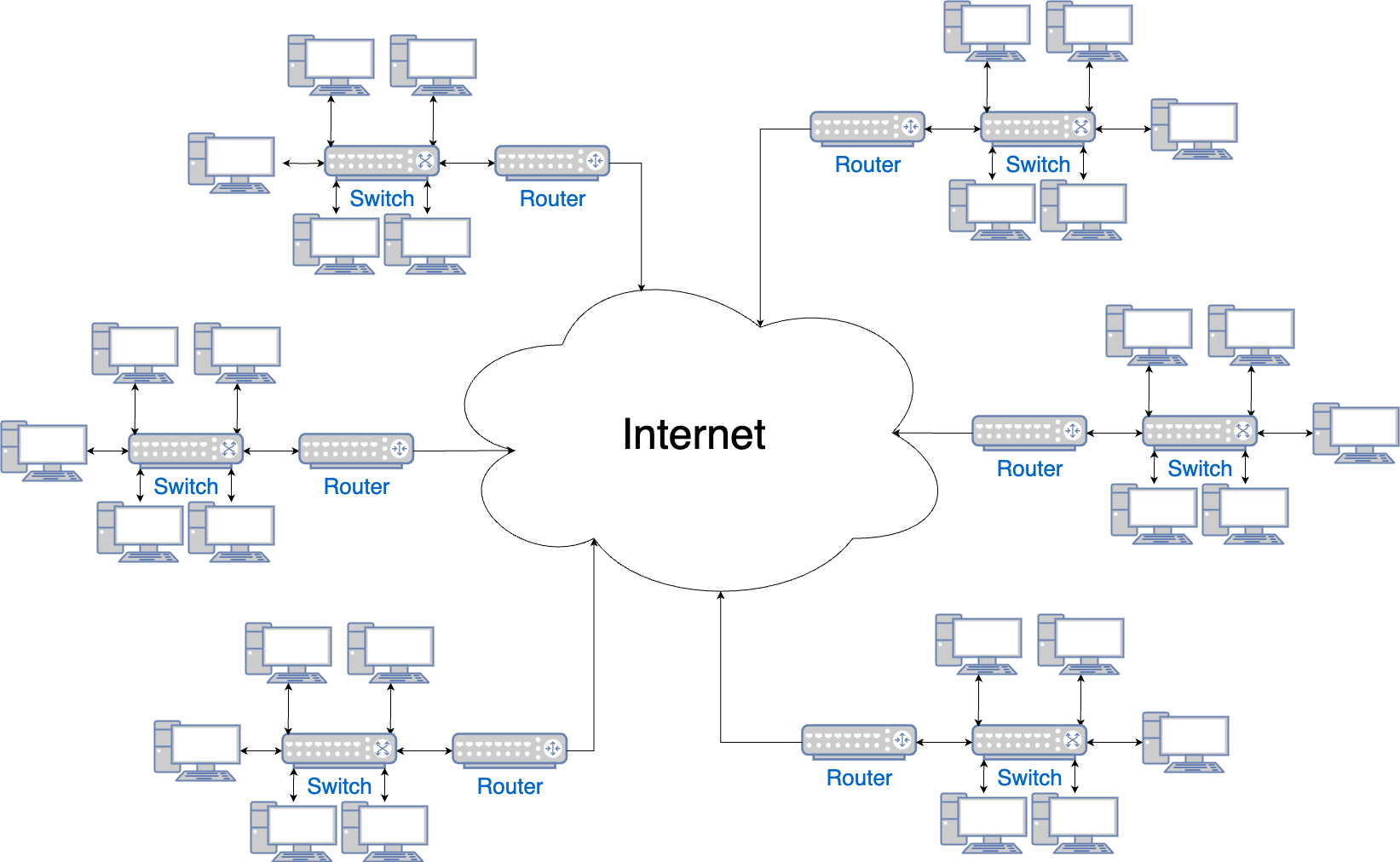

How to connect computers together?

How many computers? How to connect? Two computers

Use a single cable N computers

(aka a network)

Use a switch

(instead of $N^2$ cables)Two networks

Use two routers N networks

Use the internet19 -

Most of the networks of the internet is private network.

-

There are 2 common type of private networks:

-

Private network in your house (aka home network)

The ISP gives use a device that’s both a router & a switch, which

- allows devices in your home to talk to each other.

-

Private network in a data center:

The technicians set up various switches & routers,

- allows the servers in that the data center talk to each other.

-

Private networks’s key characteristics

Only authorized devices may connect to the private network

e.g.

-

For private network in your home:

Connect to the ISP router with

- an ethernet cable

- or Wi-Fi (with in the range of the antenna & a password)

-

For private network in a data center:

Get into the data center; plug in a cable into the routers and switches.

The private network uses private IP address ranges

The IANA reserves 3 blocks of the IP address space for private internets:

| From | To | In CIDR notation | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

10.0.0.0 | 10.255.255.255 | 10.0.0.0/8 | Class A |

172.16.0.0 | 172.31.255.255 | 172.16.0.0/12 | Class B |

192.168.0.0 | 192.168.255.255 | 192.168.0.0/16 | Class C Used in most private networks at home |

tip

With CIDR notation, the format of IPv4 address is a.b.c.d/e:

a.b.c.d: an IP addresse: a decimal number that represents how many bits of the IP address, when expressed in binary, stay the same20.

note

Every public IP address must be unique.

These 3 blocks of private IP addresses

- can be used over and over again

- as they can only used for private networks.

The private network defines connectivity rules

-

For a home network, you can define some basic control over connectivity.

e.g. Depending on your router, you can:

- Block outbound access to specific websites

- Block inbound requests from specific IP addresses

- Block specific port number from being used.

-

For a data center network,

-

you have full control over connectivity:

-

e.g. For every device (in the network), you can specify:

- What IP address it gets assigned

- What ports it’s allowed to use

- Which other devices it can talk to

- How traffic get routed to and from that device

-

using:

- hardware

- software: based on the configuration in switches, routers

-

-

-

It’s common to

- partition the private network (in a data center) into subnets

- assign specific rules to all devices in a subnet.

e.g.

- A subnet called a DMZ (demilitarized zone):

- allows access (to these servers) from the public Internet

- run a small handful of servers (such as load balancers)

- A private subnet:

- is not accessible from the public Internet

- run the rest of your servers

Most devices in a private network access the public Internet through a gateway

note

A device in a private network (with a private IP address) can also have a public IP address.

e.g. You assign a public IP address to a server in your DMZ, that server have both

- a private IP address: it uses to communicate with the devices in the DMZ

- a public IP address: it used to communicate with the Internet

-

Assigning a public IP to every device in a private network defeats the purpose of having a private network:

- keeping those devices secure

- avoiding running of of IPv4 addresses

-

Therefore, most of the devices in a private network access the public Internet through a gateway21.

Common types of gateways

Load balancers

A load balancer allows requests that

- originate from the public Internet

- to be routed to servers in your private network

- based on rules you define (in that load balancer)

e.g. If a user makes a request to the load balancer

- on port 80 for domain

foo.com, forward it to a specific app on port 8080.

NAT gateway

A Network Address Translation (NAT) gateway allows requests that

- originate in a private network

- to be routed out to the public Internet.

A common approach with NAT gateway is to do port address translation (PAT).

e.g. A server wants to make an API call to some-service.com

-

The server sends that request to the NAT Gateway, which:

- “translating” (modifying) the request to make it look like it

- originated from (the public IP of) the NAT gateway at a specific port number

- then send the modified request to

some-service.com

- “translating” (modifying) the request to make it look like it

-

When the response comes back from

some-service.com,The NAT Gateway:

- (knows which server to forward the response to)

- translate the request to make it look like it

- cam directly from

some-service.com.

- cam directly from

Outbound proxy

An outbound proxy is like a specialized NAT gateway that only allows an apps to make outbound requests to an explicitly-defined list of trusted endpoints.

note

Networking is all about layers of defense

- Most of those layers are about keeping attackers out

- An outbound proxy is the opposite - it keeps the attackers in:

- The attackers won’t be able to escape with your data.

ISP router

On your home network, the IPS router is typically configured as a NAT gateway.

- All devices send all requests to the public Internet via the ISP router, which

- also use PAT to get you response

- while keeping those devices hidden

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)

If you deploy into the cloud,

- all the physical networking: servers, cables, switches, routers…

- are already taken care of by the cloud provider

- largely in a way you can’t see or control

- are already taken care of by the cloud provider

- what you can control is a virtual private network (VPN) - a network you configure entirely in software, which makes it a software-defined networking.

Virtual networks in the cloud

Each cloud provider offers slightly different networking features, but they typically have the following basic characteristics in common:

You can create a VPN

Most cloud providers allow you to create a VPN, although they may call it different:

- For AWS, GCP: VPN is call virtual private cloud (VPC)

- For Azure: VPN is call virtual network (VNet)

note

Most of the examples in this book use AWS, so VPN will be called VPC in the rest of book.

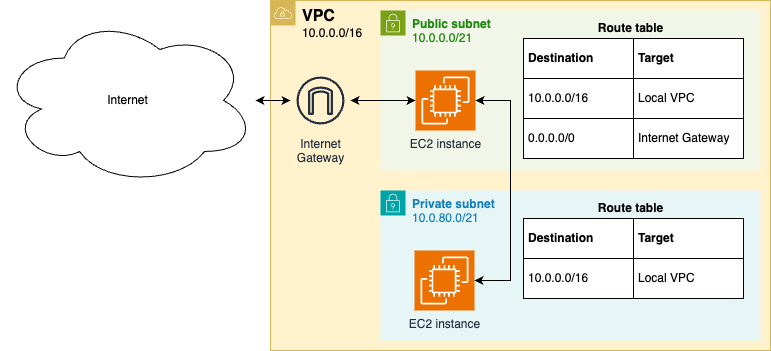

The VPC consists of subnets

Each VPC contains one or more subnets.

- Each subnet has an IP address range of the private internet as in previous section

e.g.

10.0.0.0/24

The subnets assign IP addresses

The resources deploy in a subnet will get an IP address from that subnet’s IP address range.

e.g. Three servers

- deployed in a subnet with the IP address range

10.0.0.0/24 - might have 3 IPs:

10.0.0.110.0.0.210.0.0.3

You enable connectivity with route tables

Each subnet has a route table that control how traffic is routed within that subnet.

-

Each route (in a route table) - corresponding to a row - typically defines

- a destination

- a target: where to route traffic (sent to that destination)

Route Destination Target What does it looks like? 10.0.0.0/16VPC Foo What does it exactly mean? Final target Immediate target Compare with a transit flight Paris (Final destination) Taiwan’s Airport (Transit airport)

Each time the VPC needs to route a packet, it will go through the route table, and

- use the most specific route that matches that packet’s destination (then route traffic to that route’s target)

e.g.

-

A route table with 3 routes

Destination Target 10.0.0.0/16VPC Foo 10.1.0.0/16VPC Bar 0.0.0.0/0NAT gateway - Traffic with a destination matches with

10.0.0.0/16will be routed to VPC Foo. - Traffic with a destination matches with

10.1.0.0/16will be routed to VPC Bar. - All other traffic (destination matches with

0.0.0.0/10) will be routed to the NAT Gateway (and go to the public Internet)

- Traffic with a destination matches with

You block connectivity with firewalls

Each cloud provider provides different types of firewalls to block traffic:

-

Some firewalls apply to individual resources, and typically block all traffic by default.

e.g. Each EC2 instance has a security group:

- You need to explicitly open IP/ports in the security group.

-

Other firewalls apply to entire subnets/VPCs, and typically allow all traffic by default.

e.g. AWS network firewall that filter inbound, outbound traffic across an entire VPC.

You access the public Internet through gateways

e.g. Load balancers, NAT Gateways

note

To make it easier to get started, most cloud providers allow you to deploy resources without creating a VPC.

e.g.

- AWS gives you a Default VPC out-of-the-box, which is suitable launching public instances such as a blog or simple website22

warning

To have better security and full control of the network, you should design your own networking and create your own VPC.

Virtual networks in orchestration tools

Some orchestration tools

-

include their own virtual network

e.g.

- Kubernetes Networking

- OpenShift Networking

- Marathon Networking

-

which is responsible for:

-

IP address management

Assigning IP addresses to apps (running in the orchestration tool).

-

Service communication

Allowing multiple apps (running in the orchestration tool) to communicate with each other.

-

Ingress

Allowing apps (running in the orchestration tool) to receive requests from the outside world.

-

These orchestration tools need their own virtual network because:

-

these orchestration tools are design to work in any data center or cloud

-

to solve the core orchestration problems

- that involve networking, e.g. load balancing, service communication

- in a portable way

note

When using an orchestration tool (which has its own virtual network), you have to integrate 2 sets of networking technologies:

- From the orchestration tool

- From the data center, cloud provider

To help you integrate with different cloud providers, these orchestration tools offer plugins to handle the integration.

e.g.

- Kubernetes supports:

- Container Network Interface (CNI) plugins: to manage cluster networking

- ingress controllers: to manage ingress

Comparing the behavior of networking plugins for Kubernetes in various clouds:

| Cloud | Typical CNI plugin | IP address management | Service communication | Typical ingress controller | Ingress | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWS | Amazon VPC CNI plugin | IPs from AWS VPC | Use AWS VPC routing | AWS Load Balancer Controller | Deploy AWS Elastic Load Balancers | ||

| GCP | Cilium GKE plugin | IPs from Cloud VPC subnets | Use Cloud VPC routing | GKE ingress | Deploy Cloud Load Balancers | ||

| Azure | Azure CNI plugin | IPs from VNet subnets | Use VNet routing | Nginx ingress controller | Deploy Nginx |

Example: Create a VPC in AWS

In this example, you will:

- Create a custom VPC in AWS

- Deploy some EC2 instances into it

The vpc OpenTofu module

-

from the sample code repo at

ch7/tofu/modules/vpcfolder -

can create a VPC as follow:

with the configuration for:

Configure the root module to use the vpc and ec2-instances OpenTofu modules:

-

The

vpc-ec2root module will be insamples/ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2cd examples mkdir -p ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2 cd ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2 -

Configure

main.tfto deploy a VPC and an EC2 instance in the public subnet (aka public instance)# examples/ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2/main.tf provider "aws" { region = "us-east-2" } module "vpc" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch7/tofu/modules/vpc" name = "example-vpc" # (1) cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16" # (2) }module "public_instance" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch7/tofu/modules/ec2-instances" name = "public-instance" # (1) num_instances = 1 # (2) instance_type = "t2.micro" ami_id = "ami-0900fe555666598a2" http_port = 80 user_data = file("${path.module}/user-data.sh") # (3) vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc.id # (4) subnet_id = module.vpc.public_subnet.id # (5) }Configure the instance to run:

- (4): … in the VPC created by

vpcmodule. - (5): … in the public subnet of the created VPC.

- (4): … in the VPC created by

-

The user data script (at

examples/ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2/user-data.sh)#!/usr/bin/env bash set -e curl -fsSL https://rpm.nodesource.com/setup_21.x | bash - yum install -y nodejs export MY_IP=$(hostname -I) # (1) tee app.js > /dev/null << "EOF" const http = require('http'); const server = http.createServer((req, res) => { res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' }); res.end(`Hello from ${process.env.MY_IP}!\n`); // (2) }); const port = 80; server.listen(port,() => { console.log(`Listening on port ${port}`); }); EOF nohup node app.js &- (1): Look up the private IP address of the server

- (2): Include (the private IP address of the server) in the HTTP response

-

Configure

main.tfto deploy an EC2 instance in the private subnet (aka private instance)# examples/ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2/main.tf module "private_instance" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch7/tofu/modules/ec2-instances" name = "private-instance" # (1) num_instances = 1 instance_type = "t2.micro" ami_id = "ami-0900fe555666598a2" http_port = 80 user_data = file("${path.module}/user-data.sh") vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc.id subnet_id = module.vpc.private_subnet.id # (2) } -

Output the public & private IP addresses of the EC2 instances

# examples/ch7/tofu/live/vpc-ec2/outputs.tf output "public_instance_public_ip" { description = "The public IP of the public instance" value = module.public_instance.public_ips[0] } output "public_instance_private_ip" { description = "The private IP of the public instance" value = module.public_instance.private_ips[0] } output "private_instance_public_ip" { description = "The public IP of the private instance" value = module.private_instance.public_ips[0] } output "private_instance_private_ip" { description = "The private IP of the private instance" value = module.private_instance.private_ips[0] }

-

Deploy

vpc-ec2moduletofu init tofu apply -

Verify that the instance work:

curl http://<public_instance_public_ip>

note

To be able to test the instance in the private, subnet, you’re need to know how access private network.

Get your hands dirty: Working with VPCs

Update the VPC module to

-

deploy a NAT gateway

… so that resources running in the private subnet can access the public Internet.

-

deploy each type of subnet (public and private) across multiple availability zones

… so that your architecture is resilient to the failure of a single AZ.

note

Note: AWS offers a managed NAT gateway, which works very well and is easy to use, but is not part of the AWS free tier.

Accessing Private Networks

Castle-and-Moat Model

Castle-and-moat model is the traditional approach for managing a access to private networks.

Castle-and-moat model is an analogy between:

-

a castle

- with extremely secure perimeter (moat, walls…): it’s hard to get inside

- but soft interior: once you’re inside, you can freely move around

-

a private network:

- doesn’t allow you to access anything from outside the network

- but once you’re “in” the network, you can access anything

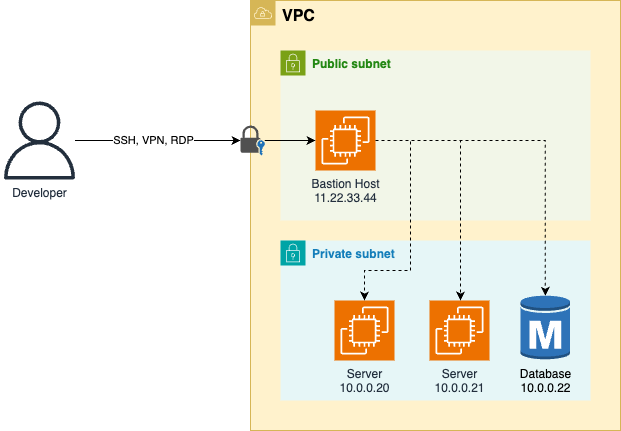

Bastion Host

In a physical network, with castle-and-moat model, merely being connected to the network means you’re in.

e.g. With many corporate office networks,

- if you’re plugged into the network via a physical cable, you can access everything in that network: wiki pages, issue tracker…

However, how do you connect to it if you’re outside the physical network:

- you’re working from home

- your’re infrastructure deployed in a VPC in the cloud

The common solution is to deploy a bastion host, a server that

-

is designed to be visible outside the network (e.g. in the DMZ)

-

has extra security hardening and monitoring, so it can better withstand attacks.

[!TIP] In a fortress, a bastion is a structure that is designed to stick out of the wall, allowing for more reinforcement and extra armaments, so that it can better withstand attacks.

The bastion host acts as the sole entrypoint to that network:

- There is only one bastion host, so you can put a lot of effort into making it as secure as possible.

- Authenticated users can

- connect to the bastion host using secured protocol (SSH, RDP, VPN)

- and have access to everything in the network.

e.g. A castle-and-moat networking model with a bastion host as the sole access point

- If you are able to connect to the bastion host (

11.22.33.44), you can access everything in the private subnets of that VPC:- The private servers (

10.0.0.20,10.0.0.21) - The database server (

10.0.0.22)

- The private servers (

Castle-and-moat model security concerns

The castle-and-moat model worked well-enough in the past, but in the modern work, it leads to security concerns.

In the past:

- Companies owns buildings with physical networks of routers, switchers, cables…

- To access that physical network, the malicious actor needs to

- be in a building owned by the company

- use a computer owned and configured by the company

note

In the past, your location on the network mattered:

- some locations could be trusted

- while others could not

Today:

- Many of the networks are virtual, e.g. VPC

- More and more employees work remotely, and needs to be able to connect to company network from a variety of locations: homes, co-working spaces, coffee shops, airports…

- Lots of devices need to connect to the company networks: laptops, workstations, tablets, phones…

The ideal of secure perimeter and soft interior no longer makes sense.

- There’s no clear “perimeter”, or “interior”

- There’s no location that can be implicitly trusted

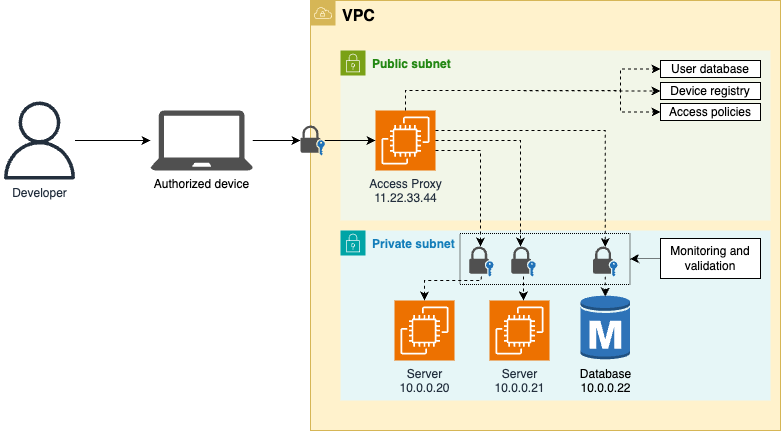

Zero-Trust Model

With zero-trust architecture (ZTA), it’s now “never trust, always verify”.

- You never trust a user or device just because they have access to some location on the network.

Core principles of zero-trust architecture (ZTA)

Authenticate every user

Every connections requires the user to authenticate, using

- single sign-on (SSO)

- multi-factor authentication (MFA)

Authenticate every device

Every connections requires the user’s device (laptop, phone, tablet) to authenticate.

You can use a lot more devices to connect, but each one still need to be

- approved,

- added to a device inventory,

- configured with adequate security controls.

Encrypt every connection

All network communicate must be over encrypted connection.

e.g. No more http

Define policies for authentication and authorization

Each piece of software (you run) can

-

define flexible policies for:

- who is allowed to access that software 👈 authentication

- what level of trust & permissions they will have 👈 authorization

-

base on a variety of data sources:

- what location is the user connecting from? Home, office or unexpected continent?

- time of the day they are connecting, e.g. Work hours, 3 a.m

- how often they are connecting? First time today or 5000 times in latst 30 seconds

Enforce least-privilege access controls

With ZTA model, you follow the principle of least privilege, which means you get access

- only to the resources you absolutely need to do a specific task,

- and nothing else

e.g. If you get access to the internal wiki, you can only access to the wiki, not the issue tracker…

Continuously monitor and validate

With ZTA, you assumes that you’re constantly under attack,

- so you need to continuously log & audit all traffic to identify suspicious behaviour.

The zero-trust model has been evolving for many years. Some of the major publications on it:

-

No More Chewy Centers: Introducing The Zero Trust Model Of Information Security by John Kindervag

The term “Zero Trust Model” came from this.

-

BeyondCorp: A New Approach to Enterprise Security by Google

This paper is arguably what popularized the zero-trust model, even though the paper doesn’t ever use that term explicitly, but the principles are largely the same.

-

Zero Trust Architecture by NIST

In the BeyondCorp paper, there are even more controversial principles:

- Google no longer requires employees working remotely to use VPN to access internal resources

- Those internal resources are accessible directly via the public Internet.

tip

By exposing internal resources to the public, Google forces itself to put more effort into securing them than merely relied on the network perimeter.

A simplified version of the architecture Google described in BeyondCorp:

-

Internal resources are exposed to the public Internet via an access proxy, which

- use user database, device registry, access policies

- to authenticate, authorize, and encrypt every single connection.

[!NOTE] This zero-trust architect might look like the castle-and-moat architecture: both reply on a single entrypoint to the network:

- For castle-and-moat approach: it’s the bastion host

- For zero-trust approach: it’s the access proxy

-

(In additional to the bastion host,) every single private resources is also protected:

To access any private resources, you need to go through the authorization process with the access proxy.

note

Instead of a singe, strong perimeter around all resources in your network, the zero-trust approach

- put a separate, strong perimeter around each individual resource.

Zero-trust should be integrated into every part of your architecture

User and device management

One of the first steps with using ZTA is to get better control over users & devices.

-

For users, you want to ensure the authentication of all the software - email, version control system, bug tracker, cloud accounts… - is done through

-

a single identity provider (SSO) that requires MFA

-

using tools like: JumpCloud, Okta, OneLogin, Duo, Microsoft Entra ID, and Ping Identity.

-

-

For devices, you want to manage the devices with a device registry:

- to track, secure, authenticate these devices

- using Mobile Device Management (MDM) tools: JumpCloud, Rippling, NinjaOne, Microsoft Intune, and Scalefusion.

Infrastructure access

For infrastructure, you need to

-

grant access to:

- servers, e.g. SSH, RDP

- databases, e.g. MySQL client, PostGres client

- containers, e.g. Docker container in Kubernetes

- networks, e.g. VPC in AWS

-

in a manner that works with zero-trust approach.

This is tricky because there’re lots if technologies in terms of protocols, authentication, authorization, encryption…

Fortunately, there’re tools like Teleport, Tailscale, Boundary, and StrongDM.

Service communication

With ZTA, you have to rework hove your (micro)services communicate with each other.

-

Many microservices (e.g. the example microservices - with a frontend and a backend - you deployed in Kubernetes) are

- designed with castle-and-moat model

- (reply on network perimeter to protect those services)

- designed with castle-and-moat model

-

This will no longer works in ZTA world, instead you need to figure out how to secure the communication between your services.

Implement a true ZTA is a tremendous effort, and very few companies are able to fully do it.

It’s a good goal for all companies to strive for, but it depends on the scale of your company:

- Smaller startups: Start with castle-and-moat approach

- Mid-sized companies: Adopt a handful of ZTA principles, e.g. SSO, securing microservices communication

- Large enterprises: Go for all ZTA principles

And remember to adapt the architecture to the needs & capabilities of your company.

important

Key takeaway #5 In the castle-and-moat model, you create a strong network perimeter to protect all the resources in your private network; in the zero-trust model, you create a strong perimeter around each individual resource.

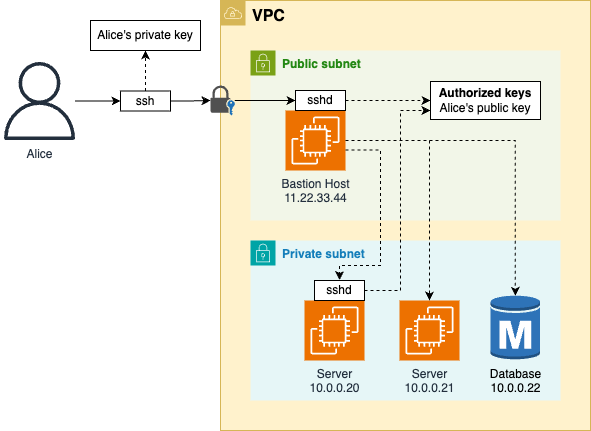

SSH

What is SSH

SSH (Secure Shell) : a protocol that allows you to connect to a computer over the network to execute commands : uses a client-server architecture

e.g. Using SSH to connect to a bastion host

-

The architecture

-

The client: computer of a developer in your team (Alice)

-

The server: the bastion host

-

When Alice connects to the bastion host over SSH,

- she gets a remote terminal, where she can:

- run commands

- access the private network

- as she was using the bastion host directly

- she gets a remote terminal, where she can:

How to use SSH

-

Configure a client, e.g. Alice’s computer

-

Configure server(s), e.g. The bastion host

-

Run SSH as a daemon27

This is typically done by running the

sshdcommand, which is enabled by default on many servers. -

Update the server’s firewall to allow SSH connections, typically on port $22$.

-

Add public keys (of Alice) to the authorized keys file of an OS user on the server.28

e.g.

- For AWS EC2 instance - default OS user is

ec2-user- you’ll need to add Alice’s public key to/home/ec2-user/.ssh/authorized_keys

- For AWS EC2 instance - default OS user is

-

-

Use SSH client to connect to the server

e.g. On Alice computer

ssh -i <PRIVATE_KEY> <OS_USER>@<SERVER_PUBLIC_IP>

After you connect to the server (e.g. the bastion host), you’ll:

-

get a terminal where you can run commands as if you were sitting directly at that server.

-

get access to that server’s network

e.g. Now Alice can

- run

curl(in the terminal) - to access the server in the private subnet at

10.0.0.20.

- run

-

tip

With SSH, you can do many more cool things:

- Transmit arbitrary data (aka tunneling)

-

Forward port (aka port forwarding)

e.g.

-

Alice use SSH to forward

- (from) port 8080 on her local computer

- (via the bastion host)

- to port 8080 of the server at

10.0.0.20(in the private subnet)

-

Any request she made from her own computer to

localhost:8080will be sent to10.0.0.20:8080.

-

-

Run a SOCKS proxy

e.g.

-

Alice

-

use SSH to run a SOCKS proxy

- on port

8080on her local computer - (via the bastion host)

- to the public Internet

- on port

-

then, configure an app that supports SOCKS proxies (e.g. a web browser )

- send all traffic via

localhost:8080(the SOCKS proxy)

- send all traffic via

-

-

When Alice uses her web browser (e.g. Chrome),

- The traffic will be routed through the bastion host, as if she was browsing the web directly from the bastion host.

With a SOCKS proxy, you can

- hide your IP from online services

- change to virtual location (aka location spoofing)

-

Example: SSH bastion host in AWS

In previous example, you deployed:

- a VPC

- 2 EC2 instances:

- one in a public subnet 👈 you could access

- one in a private subnet 👈 for now, you couldn’t access

In this example, you will update that example, so both instances can be access (over SSH)

- by using an EC2 key pair29

warning

Watch out for snakes: EC2 key pairs are not recommended in production

-

In this example, you’ll use the EC2 key-pair to experience with SSH.

-

However, AWS only supports associating a single EC2 key-pair with each C2 instance

👉 For a team, every members need to share a permanent, manually-managed private key, which is not a good security practice.

-

For production, the recommended way to connect to EC2 instance is:

Both uses automatically-managed, ephemeral key:

- generated for individual members on-demand

- expire after a short period of time

Let’s get started:

-

Create a key-pair:

-

Open the EC2 key-pairs page

-

Make sure you select the same region as the one that you deploy the VPC

-

Click

Create key pair- Enter the name for the key-pair

- Leave all settings as defaults

- Click

Create key pair

-

Download the private key (of the key-pair)

[!NOTE] AWS will store the created key-pair in its own database, but not the private key.

- It will prompt you once to download the private key.

-

Save it in a secure location, e.g.

~/.aws/.ssh

-

-

Add a passphrase to the private key, so only you can access it

ssh-keygen -p -f <KEY_PAIR>.pem -

Set the permission so the private key can be only by your OS user

chmod 400 <KEY_PAIR>.pem

-

-

Now, the only thing left is to add your public key to the authorized keys file of the root user on each of those EC2 instances.

[!TIP] If you specify a key-pair when launching an EC2 instance, AWS will add the public key to the root users of its AMIs.

-

Update the

main.tfinvpc-ec2root module to specify your key pairmodule "public_instance" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch7/tofu/modules/ec2-instances" # ... key_name = "<YOUR_KEY_PAIR_NAME>" } module "private_instance" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch7/tofu/modules/ec2-instances" # ... key_name = "<YOUR_KEY_PAIR_NAME>" }

[!NOTE] When you specify a

key_name, theec2-instancesmodule will opens up port 22 (in the security group), so you can access that instance via SSH.-

Apply the changes

tofu apply

-

Now let’s access the private instance:

-

SSH into the public instance

ssh -i <KEY_PAIR>.pem ec2-user@<PUBLIC_IP>-

Confirm you know the key-pair’s passphrase

-

Confirm you want to connect to the host

'<PUBLIC_IP>'30sshwill show use the key finder[!TIP] If you are diligent, you can manually verify that the host

<PUBLIC_IP>is really the EC2 instance deployed by you:- Go to the EC2 console

- View the system log of the instance (you’re connecting to)

- Select the instance

- In the nav op top, click

Actions>Monitor and troubleshoot>Get system log

- Verify the

SSH Host Key Fingerprintmatch with thekey fingerprintshow bysshcommand (on your local computer).

[!TIP] The fingerprint is generated from the public key.

-

You can show the fingerprint of a public key with

ssh-keygen -lssh-keygen -l -f <PUBLIC_KEY>

-

-

Now, you’re in the public instance, with a prompt like this:

Amazon Linux 2023 https://aws.amazon.com/linux/amazon-linux-2023 [ec2-user@ip-10-0-1-26 ~]$-

Check the simple web app:

curl localhost # Hello from 10.0.1.26 -

Access the private instance:

curl <PRIVATE_IP> # Hello from <PRIVATE_IP>

-

note

In this example, the public instance acts as a bastion host.

- You SSH into the bastion host, then access the private instance (from the point of view of the bastion).

You can even go a step farther, and SSH into the private instance (via the bastion host), which can be done by:

- Forwarding the SSH authentication to remote hosts (aka agent forwarding)

- Connect to a target host by first making an ssh connection to the jump host

tip

To disconnect from the SSH session:

- Send an

EOLby pressCtrl + D, or - Use the shell build-in command

exit

tip

You can use SSH agent - a key manager for SSH - to store private key in memory, so you can authenticate without specifying a key or passphrase.

-

Use

ssh-addto add a key to SSH agentssh-add <KEY_PAIR>.pem # Confirm the passphrase -

Verify that you can run SSH commands without specifying the key or passphrase

ssh -A ec2-user@<PUBLIC_IP>-

By using

-Aflag, you’re forwarding the authentication from the SSH Agent to remote machines(Local computer -> bastion host (public instance) -> private instance)

-

-

Since you’ve forwarded the SSH authentication from your local computer, you can SSH into the private instance (from the public instance)

ssh ec2-user@<PRIVATE_IP> -

Verify that’s you’re in the private instance

curl localhost # Hello from <PRIVATE_IP>

tip

To disconnect from the private instance, you need to hit Ctrl+D twice

- The first time to disconnect from the private instance

- The second time to disconnect from the public instance

Get your hands dirty: SSH

-

Instead of EC2 key pairs, try using EC2 instance connect or Session Manager

How do these options compare when connecting to the public instance? And the private instance?

-

Try using the

-Lflag to set up port forwarding from your local computer to the private server at<PRIVATE_IP>:e.g.

- run

ssh -L 8080:<PRIVATE_IP>:8080 ec2-user@<PUBLIC_IP>and - then open http://localhost:8080 in your browser.

- run

-

Try using the

-Dflag to set up a SOCKS proxy:e.g.

- run

ssh -D 8080 ec2-user@<PUBLIC_IP>, - configure your browser to use

localhost:8080as a SOCKS proxy - then open

http://<PRIVATE_IP>:8080in your browser.

- run

note

When you’ve done testing, don’t forget to run tofu destroy to clean everything up in your AWS account.

Advantages of SSH

-

Widely available

- Linux, MacOS support SSH natively

- Windows: there are also many clients

-

Secure

- SSH is a mature & secure protocol

- It has a massive community: vulnerabilities are rare and fixed quickly.

-

No extra infrastructure

Just run

sshd(which you don’t even need to install) on your server. -

Powerful dev tools

In additional to providing a way to access servers in private networks, SSH is also a daily dev tools with many features: terminal, tunneling, proxying…

Disadvantages of SSH

-

Managing keys can be difficult, especially at scale

For SSH, it’s difficult to:

- Supports hundreds of servers/developers/keys

- Key rotation and revocation

- Have different levels of permissions & access

[!TIP] There are many tools that solve this problem:

- From cloud providers:

- AWS: EC2 instance connect, Session Manager

- Google Cloud: metadata-managed SSH connections

- From cloud-agnostic 3rd-parties: Teleport, Boundary, StrongDM

-

It’s primarily a dev tool, not for everyone

SSH is not suitable for

- everyone: Product Manager, Designer…

- quickly access private network without the CLIs.

RDP

What is RDP

RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol) : a protocol that allows you to connect to a Windows computer over the network to manage it with a user interface : ~ SSH + UI (but only Windows)

How to use RDP

RDP also use client-server architecture (just like SSH):

-

Configure the RDP server:

-

Enable RDP in Windows server settings.

-

In front of the servers, deploy:

- a VPN

- or a Remote Desktop Gateway (RD Gateway)

-

Update the server’s firewall to allow RDP connects (port 3389) from previous devices.

-

Prepare the username & password of the Windows OS user account on the server:

e.g.

-

For AWS: EC2 instance - using the default Windows AMI - has an Administrator user built in with a randomly-generated password that can be retrieved from the EC2 console.

-

For Azure: you specify the username& password when launching the Windows server

-

If you’re using a identity provider (such as Active Directory, Microsoft 365), use that’s identity provider’s login.

-

-

-

Configure the RDP client:

- For Windows, the RDP client is pre-installed.

- For Mac, Linux, you needs to install the RDP client.

-

Use the RPD client to connect to the RPD server:

- Specify the IP address of the RDP Gateway/VPN

- Enter the username & password

Advantages of RDP

-

You get a fully-working Windows UI

-

Works for all employees

Disadvantages of RDP

-

Windows-only

-

Not secure without extra infrastructure

RDP has many security vulnerabilities:

- Exposing RDP port (

3389) to public Internet is not recommended. - You should run extra infrastructure (VPN or RD Gateway) in front of the RDP server .

- Exposing RDP port (

-

Not your own computer

RDP gives you access to another computer, and whatever private network it can access. But sometimes you access the private network directly from your computer (which has your apps, data).

VPN

What is VPN

VPN (Virtual Private Network) : a way to extend a private network across multiple other networks/devices

By using VPN:

- software (on any device) can communicate with the private network as if the device is “in” the network

- all traffic to the private network is encrypted (even if the traffic is over an untrusted medium, such as the public Internet)

Use cases for VPNs

Connect remote employees to an office or data center network

The VPC acts as bastion host that allow you:

- Connect to your company office network as if you were in the office

- Connect to a data center (on-prem or VPC in cloud account) as you were in the data center

VPN vendors of this use case: Cisco, Palo Alto Networks, Juniper Networks, Barracuda, SonicWall, Fortinet, OpenVPN, WireGuard, Tailscale, AWS Client VPN, and Google Cloud VPN.

Connect two data centers together

A site-to-site VPN can connect 2 data centers together.

e.g.

- 2 on-prem data centers connects together

- An on-prem data center connect to a VPC in the cloud

The VPC acts as a proxy between the data centers:

- Securely forwarding

- certain traffic in one private network

- to certain endpoints in another private network

This use case needs 2 type of VPN vendors:

- On the on-prem side: the same as office network, e.g. Cisco, Palo Alto, Juniper

- On the cloud side: site-to-site VPN services from cloud provider, e.g. AWS Virtual Private Gateways, Google Cloud VPN.

Hide Internet browsing behavior

You can use a VPN as a way to

- bypass geographical restrictions, or censorship

- keep your browsing history anonymous

The office network VPNs are overkill for this use case, it’s more common to use consumer VPN services, e.g. NordVPN, ProtonVPN, ExpressVPN.

How to use VPN

To connect remote employees to an office

The VPN for this use case is typically use a client-server architecture

-

Configure the VPN server

-

Deploy a VPN server (as the bastion host) and configure VPN software on it

-

Update the server’s firewall to alow VPN connections:

e.g.

- VPNs based on IPSec will use ports

500,4500,50,51… - VPNs based on TLS will use port

443

- VPNs based on IPSec will use ports

-

Configure the VPN server with the ability to authenticate users

e.g.

-

Traditional approach, used by old tool (e.g. OpenVPN):

- use certificates (based on public-key cryptography)

- but allow mutual authentication31

This approach is hard to securely sign, distribute, revoke/manage certificates.

-

Modern approach, used by new tool (e.g. Tailscale), allow users to authenticate

- using existing identity provider (e.g. Active Directory, Google, Okta)

- including MFA

under the hood, the certificate logic is handle transparently.

-

-

-

Configure the VPC client

-

Install the VPN client:

It’s usually a desktop/mobile app (with UI). Some OSes even have VPN clients built-in.

-

Following the VPN client’s instruction (in the UI) to authenticate.

-

Once configured/authenticated, the VPN will:

-

establish an encrypted tunnel to the VPN server

-

update the device’s networking settings to

-

route all network traffic through this tunnel (aka full tunnel mode)

[!WARNING] In split tunnel mode, all traffic (whether it from your working software or Youtube/Netflix) will be routed through the VPN, which may

- put a lot of load on VPN server

- cost a lot of bandwidth (and money)

[!NOTE] Some VPN client supports split tunnel mode, where only certain traffic is routed to the VPN server e.g.

- Only some traffic for specific domain names and CIDR block that corresponding to your company internal software go though the VPN tunnel

- Everything else goes through public Internet.

-

-

-

To connect two data centers

The high level steps looks like this:

-

Setup a site-to-site VPN device

In an on-prem data center, it might be a physical appliance from Cisco, Palo Alto, Juniper…

In the cloud, it’s be a virtual configuration, e.g. Virtual Private Gateway in AWS.

-

Configure routing

Route certain CIDR blocks from one data center (through the VPN connection) to the other data center.

e.g.

- On-prem data center network uses CIDR block

172.16.0.0/12. - Configure the route table in AWS VPC to route all traffic with destiantion match that CIDR block

172.16.0.0/12to your Virtual Private Gateway.

- On-prem data center network uses CIDR block

-

Configure connectivity and authentication

For each data center, you’ll need configure

- IP address

- Identifying information: Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) Autonomous System Number (ASNs)

- a way to authenticate & encrypt the connection

-

Create the VPN tunnel

Advantages of VPN

-

You get network transparent32 access from your own computer

With VPN, you can access a private network, from your own computer, as if you were directly a part of that network.

-

Works for all employees

-

Works with all operating systems

-

Secure

Most VPN tools are build around IPSec or TLS, both are mature and secure.

Disadvantages of VPN

-

Extra infrastructure to run

You have to deploy a VPN server, possibly multiple servers for high availability.

-

Certificate management can be difficult

Most VPN tools are build around certificates, which is difficult to manage.

-

Performance overhead

- Traffic a route through another server, which increase latency.

- Too much traffic may degrade your network throughput.

Service Communication in Private Networks

In chapter 6, you saw that a common way to deal with problems of scale (more traffic, more employees), is to

- break codebase into multiple (micro)services that are

- deployed independently, typically on separates servers.

These services communicate (with each other) by sending messages over the network.

In order to allow services communicate over the network, you have to make following technical decisions:

| The technical decision | What does it mean? |

|---|---|

| Service discovery | How (one service know what endpoint) to reach another service? |

| Service communication protocol | What is the format of the messages (that a service send to another service)? |

| Service mesh | How to handle security, resiliency, observability, traffic management? |

Service Discovery

Although service discovery may looks easy

- to talk with service B, service A only needs service B’s IP address

but when you have:

- multiple services

- each with multiple replicas that

- runs on multiple servers

- each with multiple replicas that

- the number of replicas, servers change frequently as:

- you deploy new versions

- replicas crashed and replaced

- you scale up/down

- …

service discovery can be a challenging problem.

important

Key takeaway #6 As soon as you have more than one service, you will need to figure out a service discovery solution.

Service discovery tools

Generic tools

Configuration files

The simplest soluction is to hard-coded server IP address in configuration files.

e.g.

- Service A have a config file with hard-coded IP address of the servers where B is deployed.

note

This works as long as the IP address used by B don’t change too ofter, such as

- an on-prem data center

- in the cloud but you’re using private static IP address for B’s virtual servers

(Internal) load balancers

You can:

- deploy an internal load balancers in front of all services.

- hard-code the endpoints of the load balancer (for each environment).

Then service discovery can be done by using:

-

a convention for the path

e.g.

- Service A reaches service B at

/Bpath of the load balancer.

- Service A reaches service B at

DNS

tip

Service discovery is about translating a name (of the service) to a set of IP addresses.

Isn’t it the DNS?

You can

- use a private DNS server (from the cloud provider)

- create a DNS record that points to the IP address for each service

Then service discovery can be done by using:

-

a convention for the domain

e.g.

- Service A reach service B at the domain

B.internal

- Service A reach service B at the domain

Dedicated service discovery tools

Service discovery tools with service discovery library

Tool sucs as Consul, Curator and ZooKeeper, Eureka comes with 2 components:

-

a service registry: a data store that

- stores the endpoint data for services

- performs health checks (to detech when endpoints are up & down)

- allows services to subscribe to updates (and notify immediately when endpoints are updates)

-

the service discovery library: a library you incorporate into your application code to:

- add endpoints (to the service registry) when your services ares booting

- fetch endpoint data (from the service registry)

- subscribe to updates 👉 you can make service calls by looking up the latest service endpoint data in memory

Service discovery tools with local proxy

Tools such as

-

built-in mechanism of orchestration tools

e.g.

- Kubernetes and the platforms built on top of it (EKS, GKE, AKS…)

- Nomad, Mesos

come with 2 components:

- a service registry (same as service discovery library)

- a local proxy: a proxy that run on the same servers as your apps, by:

- deploying it as a sidebar container33 (~ in another container)

- or running it as a daemon (in the same container)

These local proxy:

- does the exactly same thing as the server discovery library: add endpoints, fetch endpoints, subscribe to updates.

- but

- is completely transparent (to the application)

- does not requires any changes to your application code.

To use a local proxy,

-

you:

- override network settings in each container/server to send all traffic throug this proxy

- or use the proxy as a local DNS server

-

the local proxy

- uses its local service registry data

- to route your app’s requests to the proper endpoints

- without the app be aware of the service discovery tool - local proxy

Service discovery tool comparison

The key trade-offs to consider when picking a service discovery tool:

| Trade-off | What to consider? | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Manual error | Any solution that involves hard-coding data is error-prone. | |

| Update speed | - Hard-code IPs: slow | |

| - DNS: low TTL -> faster with the cost of latency | ||

| - Dedicated service discovery tools: subscribe -> quickly | ||

| Scalability | - Hard-code IPs: always hit scaling bottlenecks | |

| - Load balancers: difficult to scale if you have lots of traffic | ||

| Transparency | - Some tools require you to update your code app | To incorporate service discovery logic |

| - Other tools don’t require you to update your code (called transparent) | The code app still need to use some mechanis to make a service call | |

| Latency | - DNS: add an extra network hop (the DNS server) | You can cache the DNS response, but that reduces update speed |

| - Service-side tools (load balancers): requires extra network hops -> increase latency | ||

| - Client-side tools (library): endpoints are cache locally -> no extra network hops | ||

| - Local proxy: also has an extra hop, but it’s locally | ||

| CPU, memory usage | - Local proxy: extra code run with every container/servers | |

| Extra infrastructure | - Load balancer, service registry: requires deploying/managing extra infrastructure |

| Configuration files | Load balancers | DNS | Registry + Library | Registry + Local proxy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⬇️ Manual error | ❌ | ⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| Update speed | ❌ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| Scalability | ❌ | ⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| Transparency to app | ⭐ | ⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ❌ | ⭐⭐⭐ |

| ⬇️ Latency overhead | ⭐⭐⭐ | ❌ | ⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ |

| ⬇️ CPU, memory overhead | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ❌ |

| ⬇️ Infrastructure overhead | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐ | ⭐⭐ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Sign | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ❌ | Poor |

| ⭐ | Moderate |

| ⭐⭐ | Strong |

| ⭐⭐⭐ | Very Strong |

Service Communication Protocol

Message encoding vs Network encoding

Breaking codebase into services 👈 Define/maintain APIs 👈 Protocol decisions for APIs

message encoding : How will you serialize34 data? : e.g. JSON, Protocol Buffers; HTML, XML

network encoding : How will you send that data over the network? : e.g. HTTP, HTTP/2

Common protocols for Service Communication

REST APIs: HTTP + JSON

REST : Representation State Transfer : de factor standard for building web APIs

For REST:

- network encoding: HTTP

- message encoding: JSON (or HTML)

Serialization libraries

Serialization libraries supports:

- defining a schema

- compling stubs for various programming languages

e.g. Protocol Buffers, Cap’n Proto 35, FlatBuffers 36, Thrift, Avro

Serialization libraries:

- can use HTTP

- but for better performance: they will use HTTP/2

RPC libraries

RPCs libraries : one level up from serialization libraries : designed for remote procedure call (RPC), where : - a calling to a remote procedure, is : - the same as a calling to a local procedure : generate both client & server stubs : HTTP/2 + Protocol Buffers

e.g. gRPC, Connect RPC, drpc, Twirp

| Examples | Network encoding | Message encoding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| REST | HTTP | JSON | |

| Serialization libraries | HTTP/2 | Protocol Buffers, Cap’n Proto, FlatBuffers… | |

| RPC libraries | gRPC, Connect RPC | HTTP/2 | Protocol Buffers |

Key factors of Service Communication Protocol

| Key factor | What to consider? | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Programming language support | - Which programming languages are used at your company? | |

| - Does they support the message encoding you need? | - JSON: is supported by almost any programming languages- Serizization protocols: are supported in popular ones | |

| Client support | - Which clients do your APIs need to support? | - Web browsers, mobiles, IoT… |

| - Which protocols do these clients support? | - HTTP + JSON: every clients, native to web browsers- Serizization protocols: hit or miss, especially with web browsers | |

| Schema and code generation | Does the message encoding supports: | |

| - defining a schema? | - HTTP + JSON: doesn’t support (but can use other tools, e.g. OpenAPI)- Serialization/RPC libraries: strong | |

| - generate client stubs? | ||

| - generate documentation? | ||

| Ease of debugging | How hard is it to test an API (built with this tool) or to debug problems? | - HTTP + JSON: easy, any HTTP client can be used: - web browser - UI tools, e.g. Postman - CLI tools, e.g. curl |

- Serialization/RPC libraries: require special tooling | ||

| Performance | How efficient are the message/network encoding in terms of bandwidth/memory/CPU usage? | HTTP + JSON < Serialization/RPC libraries |

| Ecosystem | - Documentation? Updates? | - HTTP + JSON: largest ecosystem |

| - Tools, plugin, related projects | - Serialization/RPC libraries: small | |

| - Hire new developers | ||

| - Find answers on the Internet (StackOverflow) | ||

tip

The generate rule is:

-

Use HTTP + JSON for most APIs

-

Only consider alternatives in special cases

e.g. At very large scales:

- hundreds of servies

- thousands of queries per second

Service Mesh

What is a service mesh

service mesh : a networking layer that help manage communication betweens micro(services)

Why use a service mesh

A service mesh provides a single, unified solution for many problems:

-

Security

In Chapter 6 - Example: Deploy Microservices In Kubernetes,

- as long as someone has network access (to your cluster)

- they could talk to any service (in your cluster) (the services respond blindly to any request came in)

You can have some level of protection by:

- putting these microservices in a private network 👈 castle-and-moat model

- hardening the security by enforcing encryption, authentication, authorization 👈 zero-trust model

-

Observability

With (micro)services architecture,

-

Debugging a failure/bug is hard:

- A single request may result in dozens of API calls to dozens of services.

- There are many new failure modes because of the network.

-

Observability tools: tracing, metrics, logging… become essensial.

-

-

Resiliency

The more services you have; the more bugs, issues, errors happens.

- If you have to manually deal with every bugs, issues, errors, you’d never be able to sleep.

To have a maintainable, resilient (micro)services, you need tools/techniques to:

- avoid

- recover

errors automtatically.

e.g. retries, timoutes, circuit breakers, rate limiting

-

Traffic management

(Micro)services is a distributed system.

To manage a large distributed system, you need a lot of fine-grained control over network traffic.

e.g.

-

Load balancing between services

e.g. ⬇️ latency, ⬆️ throughput

-

Canary deployment

e.g. Send traffic to a new replica (of an app as in Chap 5 - Canary Deployment)

-

Traffic mirroring

e.g. Duplicate traffic to an extra endpoint for analysis/testing

-

Almost all of these are problems of scale:

-

If you are a small team, with only some services and not much of load

1️⃣ in other words, when you don’t have the scaling problems, a service mesh

- don’t help you

- but it may be an unnecessary overhead.

-

If there are hundreds of services owned by dozens of teams, processing thousands of requets per seconds,

-

in other words, when you have scaling problems:

2️⃣ you may try to solve these problems individually, one at a time, but it will

- be a huge amount of work 👈 each problems needs its own tool, solution…

- that have many frictions 👈 each change is a global changes to every single service…

- take a very long time 👈 … rolling global change across services is a big challenge

3️⃣ or you can use a service mesh - all-in-one solutions to the these scaling problems

- in a transparent way

- does not require making changes to application code

-

important

Key takeaway #7 A service mesh can improve a microservices architecture’s

- security, observability, resiliency, and traffic management

without having to update the application code of each service.

When not to use a service mesh

A service mesh can feel like a magical way to dramatically upgrade the security and debuggability of your (micro)service architecture.

- But when things doesn’t work, the service mesh itself can be difficult to debug.