Chapter 6: How to Work with Multiple Teams and Environments

-

CI/CD will allow developers work together efficiently and safety,

-

but as your company grows, there are other type of problems:

- From outside world: more users (more traffic/data/laws/regulations)

- From inside your company: more developers/teams/products 👉 It’s harder to code/test/deploy without hitting lots of bugs/outages/bottlenecks.

-

-

These problems are problems of scale,

- (good problems to have, which indicates your business is becoming more successful).

-

The most common approach to solve these problem of scale is divide and conquer:

- Break up your deployments: into multiple separated, isolated environments.

- Break up your codebase: into multiple libraries, (micro)services

Breaking Up Your Deployments

- In this book, you deploy everything - servers, Kubernetes, cluster, serverless functions, … - into a single AWS account 👈 Fine for learning & testing

- In real world, it’s common to have multiple deployment environments, each environment has its own set of isolated infrastructure.

Why Deploy Across Multiple Environments

Isolating Tests

-

Typically, you need a way to test changes to your software

- before you expose those changes (to users)

- in a way that limits the blast radius (that affects users, production environment).

-

You do that by deploying more environments that closely resemble production.

-

A common setup is having 3 environments:

-

Production: the environment that is exposed to users.

-

Staging: a scaled-down clone of production that is exposed to inside your company.

👉 The releases are staged in staging so other teams - e.g. QA - can test them.

-

Development: another scaled-down clone of production that is exposed to dev team.

👉 Dev teams test code changes in development during development process (before those changes make it to staging).

-

tip

These trio environments have many other names:

- Production:

prod - Staging:

stage,QA - Development:

dev

Isolating Products and Teams

-

Larger companies often have multiple products and teams,

- which may have different requirements in term of uptime, deployment frequency, security, compliance…

-

It’s common for each team/product to have its own isolated set of environments, so:

- each team can customize to their own needs

- limit the blast radius of each team/product

- allows teams to work in isolated from each other (which may be good or bad!)

-

e.g.

- Search team have their software deployed in

search-dev,search-stage,search-prodenvironments. - Profile team have their software deployed in

profile-dev,profile-stage,profile-prodenvironments.

- Search team have their software deployed in

important

Key takeaway #1 Breaking up your deployment into multiple environments allows you to isolate tests from production and teams from each other.

Reducing Latency

What is latency

-

Data needs to travel from users’s device to your servers and back.

- This is measured with a TCP packet round trip (from your server and user device) - aka network latency.

-

Although these TCP packages is traveling at nearly the speed of light,

-

when you build software used across the globe

-

the speed of light is still not fast enough

-

this network latency may become the biggest bottleneck of your software.

Operation How much? Where? Time in (μs) Notes Read (Random) from CPU cache (L1) 0.001 Read (Random) from DRAM - main memory 0.1 Compress with Snappy $1 KB$ 2 Read (Sequentially) $1 MB$ from DRAM 3 Read (Random) from SSD - solid state disk 16 Read (Sequentially) $1 MB$ from SSD 49 TCP packet round trip $1.5 KB$ within same data-center 500 0.5 ms Read (Random) from HDD - rotational disk 2,000 Read (Sequentially) $1 MB$ from HDD 5,000 TCP packet round trip $1.5 KB$ from California to New York

(1 continent)40,000 40 ms TCP packet round trip $1.5 KB$ from California to Australia

(2 continents)183,000 183 ms

-

-

How to reduce latency

-

If you have users around the world,

- you may run your software on server (and data center) that geographically close to those users,

- to reduce the latency1.

- you may run your software on server (and data center) that geographically close to those users,

-

e.g.

- By having the servers in the same continent with your user,

- the latency for each TCP package is reduced more than 100 ms.

- when including the fact that most web page, application sends:

- thousands of KB in size (across many requests)

- this network latency can quickly add up.

- By having the servers in the same continent with your user,

Complying With Local Laws and Regulations

Some countries, industries, customers requires your environments be set up in a specific ways, e.g:

- In EU: GDPR2

- Store/process credit card: PCI DSS3.

- Store/process healthcare information: HIPAA4, HITRUST5

- US government: FedRAMP6

A common pattern is to set up a dedicated, small environment for complying with laws & regulations.

e.g.

prod-pci: meets all the PCI DSS requirements, and is used solely to run payment processing softwareprod: run all other software

Increasing Resiliency

- With only 1 environments, you can still have some level of resilient by having multiple servers. But all these servers can have a single point of failure (the data center that the environment is in).

- By having multiple environments in different data center around the world (e.g.

prod-us,prod-eu,prod-asia), you can have a higher level of resilient.

How to Set Up Multiple Environments

Logical Environments

logical environment : an environment defined solely in software (i.e., through naming and permissions), whereas the underlying hardware (servers, networks, data centers) is unchanged

e.g.

- In Kubernetes, you can create multiple logical environments with namespaces.

tip

In Kubernetes, if you don’t specify a namespace, the namespace default will be used.

-

To create a namespace, use

kubectl createkubectl create namespace <NAME> -

Specify the namespace to

kubectl’s sub-command, e.g.# deploy an app into the development environment kubectl apply --namespace dev # or deploy an app into the staging environment kubectl apply --namespace stg

Separate Servers

You set up each environment in a separate server.

e.g.

-

(Instead of a single Kubernetes cluster for all environments)

-

You deploy one Kubernetes cluster per environment

- Deploy Kubernetes cluster

devindev-servers - Deploy Kubernetes cluster

stginstg-servers

- Deploy Kubernetes cluster

tip

You can go a step further by deploying control plane and worker nodes in separate servers.

Separate Networks

You can put the servers in each environment in a separate, isolated network.

e.g.

- The servers in

dev-envcan only communicate with other servers indev-env. - The servers in

stg-envcan only communicate with other servers instg-env.

Separate Accounts

If you deploy into the clouds, you can create multiple accounts, each account for an environment.

note

By default, cloud “accounts” are completely isolated from each other, including: servers, networks, permissions…

tip

The term “account” can be different for each cloud provider:

- AWS: account

- Azure: subscription

- Google Cloud: project

Separate Data Centers In The Same Geographical Region

If you deploy into the clouds, you can deploy environments in different data centers that are all in the same geographical region.

e.g.

- For AWS, there are

use1-az1,use1-az2,use1-az37

tip

For AWs, data centers that are all in the same geographical region are called Availability Zones - AZs

Separate Data Centers In Different Geographical Regions

If you deploy into the clouds, you can deploy environments in different data centers that are in the different geographical regions.

e.g.

- For AWS, there are

us-east-1,us-west-1,eu-west-1,ap-southeast-1,af-south-18

tip

For AWS, different geographical regions are call regions.

How Should You Set Up Multiple Environments

-

Each approach to set up multiple environments has advantages and drawbacks.

-

When choosing your approach, consider these dimensions:

-

What is the isolated level?

~ How isolated one environment is from another?

- Could a bug in

dev-envsomehow affectprod-env.

- Could a bug in

-

What is the resiliency?

~ How well the environment tolerate an outage? A server, network, or the entire data center goes down?

-

Do you need to reduce latency to users? Comply with laws & regulations?

~ Only some approaches can do this.

-

What is the operational overhead? ~ What is the cost to set up, maintain, pay for?

-

Challenges with Multiple Environments

Increased Operational Overhead

When you have multiple environments, there’re a lot of works to set up and maintain:

- More servers

- More data centers

- More people

- …

Even when you’re using the clouds - which offload much of this overhead (into cloud providers) - creating & managing multiple AWS accounts still has its own overhead:

- Authentication, authorization

- Networking

- Security tooling

- Audit logging

- …

Increased Data Storage Complexity

If you have multiple environments in different geographical regions (around the world):

-

The latency between the data centers and users may be reduced,

- but the latency between parts of your software running in these data centers will be increased.

-

You may be forced to rework your software architecture completely, especially data storage.

e.g. A web app that needed to lookup data in a database before sending a response:

-

When the database and the web app is in the same data center:

~ The network latency for each package round-trip is 0.5ms.

-

When the database and the web app is in different data centers (in different geographical regions):

~ The network latency for each package round-trip is 183ms (366x increase), which will quickly add up for multiple packets.

-

When the database and the web app is in different data centers (in different geographical regions), but the database is in the same region as the web app:

~ In other words, you have one database per region, which adds a lot to your data storage complexity:

- How to generate primary keys?

- How to look up data?

- Querying & joining multiple databases is more complicated.

- How to handle data consistency & concurrency?

- Uniqueness constraints, foreign key constraints

- Locking, transaction

- …

To solve these data storage problems, you can:

- Running the databases in active/standby mode9, which may boost resiliency, but doesn’t help with the origin problems (latency or laws, regulations).

- Running the databases in active/active mode10, which also solves the origin problems (latency or laws, regulations), but now you need to solve more problems about data storages.

important

Key takeaway #2 Breaking up your deployment into multiple regions:

- allows you to reduce latency, increase resiliency, and comply with local laws and regulations,

- but usually at the cost of having to rework your entire architecture.

Increased Application Configuration Complexity

-

When you have multiple environments, you have many unexpected costs in configuring your environments.

-

Each environment needs many different configuration:

Type of settings The settings Performance settings CPU, memory, hard-drive, garbage collection… Security settings Database passwords, API keys, TLS certifications… Networking settings IP address/domain name, port… Service discovery settings The networking settings to use for other services you reply on… Feature settings Feature toggles… -

Pushing configuration changes is just as risky as pushing code changes (pushing a new binary), and the longer a system has been around, the more configuration changes tend to become the dominant cause of outages.

[!TIP] Configuration changes are one of the biggest causes of outages at Google11.

Cause Percent of outages Binary push 37% Configuration push 31% User behavior change 9% Processing pipeline 6% Service provider chang 5% Performance decay 5% Capacity management 5% Hardware 2% [!IMPORTANT] Key takeaway #3 Configuration changes are just as likely to cause outages as code changes.

How to configure your application

-

There a 2 methods of configuring application:

-

At build time: configuration files checked into version control (along with the source code of the app).

[!NOTE] When checked into version control, the configuration files can be:

- In the same language as the code, e.g. Ruby…

- In a language-agnostic format, e.g. JSON, YAML, TOML, XML, Cue, Jsonnet, Dhall…

-

At run time: configuration data read from a data store (when the app is booting up or while it is running).

[!NOTE] When stored in a data store, the configuration files can be stored:

- In a general-purpose data store, e.g. MySQL, Postgres, Redis…

- In a data store specifically designed for configuration data, e.g. Consul, etcd, Zookeeper…

[!TIP] The data store specifically designed for configuration data allows updating your app quickly when a configuration changed

- Your app subscribes to change notifications.

- Your app is notified as soon as any configuration changes.

-

-

In other words, there 2 types of configuration:

- Build-time configuration.

- Run-time configuration.

-

You should use build-time configuration as much as possible:

Every build-time configuration is checked into version control, get code reviewed, and go through your entire CI/CD pipeline.

-

Only using run-time configuration when the configuration changes very frequently, e.g. service discovery, feature toggles.

Example: Set Up Multiple Environments with AWS Accounts

note

IAM and environments

-

IAM has no notion of environments

Almost everything in an AWS account is managed via API calls, and by default, AWS APIs have no first-class notion of environments, so your changes can affect anything in the entire account.

-

IAM is powerful

- You can use various IAM features - such as tags, conditions, permission boundaries, and SCPs - to create your own notion of environments and enforce isolation between them, even in a single account.

- However, to be powerful, IAM is very complicated. Teams can mis-use IAM, which leads to disastrous results.

note

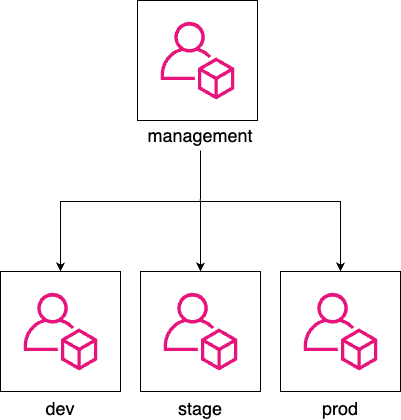

The recommend way to organize multiple AWS environments is using multiple AWS accounts12:

- You use AWS Organizations to create and manage your AWS accounts,

- with one account at the root of the organization, called the management account,

- and all other accounts as child accounts of the root.

e.g.

-

An AWS organization with one management account (

management), and 3 child accounts (e.g.,dev,stage,prod)

tip

Using multiple AWS accounts gives you isolation between environments by default, so you’re much less likely to get it wrong.

Create child accounts

In this example, you will

-

Treat the initial AWS account as the management account

[!CAUTION] The management account should only be used to create & manage other AWS accounts.

-

Configure initial account as the management account of an AWS Organization.

-

Use AWS Organizations to create 3 other accounts as child accounts (for

dev,stage,prod).

To treat the initial AWS account as the management account, you need to undeploy everything deployed in earlier chapters:

- Run

tofu destroyon any OpenTofu modules previously deployed. - Use EC2 Console to manually undeploy anything deployed via Ansible, Bash…

-

The code for this example (the OpenTofu

child-accountsroot module) will be intofu/live/child-accountsfolder:mkdir -p ch6/tofu/live/child-accounts cd ch6/tofu/live/child-accounts[!TIP] Under the hood, the root module will use the OpenTofu module

aws-organizationsin the sample code repo atch6/tofu/modules/aws-organizationsfolder. -

The OpenTofu module

main.tf# examples/ch6/tofu/live/child-accounts/main.tf provider "aws" { region = "us-east-2" } module "child_accounts" { # (1) source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch6/tofu/modules/aws-organization" # (2) Set to false if you already enabled AWS Organizations in your account create_organization = true # (3) TODO: fill in your own account emails! dev_account_email = "username+dev@email.com" stage_account_email = "username+stage@email.com" prod_account_email = "username+prod@email.com" }-

(1): Use the

aws-organizationmodule. -

(2): Enable AWS Organizations before using it.

-

(3): Fill in root user’s email address for

dev,stage,prodaccounts.[!TIP] If you’re using Gmail, you can create multiple aliases for a a single email address by using plus sign (

+).

-

-

Proxy output variables from the

aws-organizationmodule# examples/ch6/tofu/live/child-accounts/outputs.tf # (1) output "dev_account_id" { description = "The ID of the dev account" value = module.child_accounts.dev_account_id } output "stage_account_id" { description = "The ID of the stage account" value = module.child_accounts.stage_account_id } output "prod_account_id" { description = "The ID of the prod account" value = module.child_accounts.prod_account_id } # (2) output "dev_role_arn" { description = "The ARN of the IAM role you can use to manage dev from management account" value = module.child_accounts.dev_role_arn } output "stage_role_arn" { description = "The ARN of the IAM role you can use to manage stage from management account" value = module.child_accounts.stage_role_arn } output "prod_role_arn" { description = "The ARN of the IAM role you can use to manage prod from management account" value = module.child_accounts.prod_role_arn }- (1): The IDs of created accounts

- (2): The IAM role’s ARN used to manage child accounts from management account.

-

Deploy

child-accountsmoduletofu init tofu apply

Access your child accounts

To access child accounts, you need to assume the IAM role that has permission to access them (OrganizationAccountAccessRole).

To assume the IAM role OrganizationAccountAccessRole, you can use:

-

AWS Web Console:

- Click your username / Choose

Switch role - Enter the information to switch role:

- account ID

- IAM Role

- display name

- display color

- Click

Switch role

- Click your username / Choose

-

Terminal:

One way to assume IAM role in the terminal is to configure an AWS profile (in the AWS config file) for each child account.

[!TIP] The AWS config file is default at

~/.aws/confige.g. To assume IAM role for

devchild account:-

Create an AWS profile named

dev-admin[profile dev-admin] # (1) role_arn=arn:aws:iam::<ID>:role/OrganizationAccountAccessRole # (2) credential_source=Environment # (3)- (1): The AWS profile will be named

dev-admin. - (2): The IAM role that this profile will assume.

- (3): Use the environment variable as credential source.

- (1): The AWS profile will be named

-

Specify the profile when you use AWS CLI with

--profileargumente.g. Use

aws sts get-caller-identitycommand to get the identity of thedev-adminprofileaws sts get-caller-identity --profile dev-admin

-

Deploy into your child accounts

Now you will re-deploy the lambda-sample module into dev, stage, prod accounts.

-

Copy the

lambda-samplemodule (and its dependencytest-endpointmodule) from chapter 5cd fundamentals-of-devops/examples mkdir -p ch6/tofu/live cp -r ch5/tofu/live/lambda-sample ch6/tofu/live mkdir -p ch6/tofu/modules cp -r ch5/tofu/modules/test-endpoint ch6/tofu/modules -

Update to copied module to use new path

# ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/backend.tf key = "ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample" -

Add support for AWS profiles

# ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/variables.tf variable "aws_profile" { description = "If specified, the profile to use to authenticate to AWS." type = string default = null }# ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/main.tf provider "aws" { region = "us-east-2" profile = var.aws_profile }[!NOTE] Later, you will specify the AWS profile via

-var aws_profile=XXXflag when runningtofu apply. -

Dynamically show the environment name

-

Update the Lambda function to response with the environment name

// examples/ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/src/index.js exports.handler = (event, context, callback) => { callback(null, { statusCode: 200, body: `Hello from ${process.env.NODE_ENV}!`, }); }; -

Dynamically set the

NODE_ENVto the value ofterraform.workspace# examples/ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/main.tf module "function" { source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch3/tofu/modules/lambda" # ... (other params omitted) ... environment_variables = { NODE_ENV = terraform.workspace } }[!NOTE] What is OpenTofu workspace?

-

In OpenTofu, you can use workspaces to manage

- multiple deployments of the same configuration.

-

Each workspace:

- has its own state file

- represents a separate copy of all the infrastructure

- has a unique name (returned by

terraform.workspace)

-

If you don’t specify a workspace explicitly, you end up using a workspace called

default.

-

-

-

(Optional) Authenticate to your management account

-

Initialize the OpenTofu module

cd examples/ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample tofu init -

Create a new workspace for

devenvironment and deploy the environment to thedevaccount:-

Create workspace

tofu workspace new development -

Deploy infrastructure and the lambda function

tofu apply -var aws_profile=dev-admin -

Verify that the lambda function works

curl <DEV_URL>

-

-

Do the same for

stageandprodenvironmentstofu workspace new stage tofu apply -var aws_profile=stage-admin curl <STAGE_URL>tofu workspace new production tofu apply -var aws_profile=prod-admin curl <PROD_URL> -

Congratulation, you have three environments, across three AWS accounts, with a separate copy of the serverless webapp in each one, and the OpenTofu code to manage it all.

Use different configurations for different environments

In this example, to have different configurations for different environments, you’ll use JSON configuration files checked into version control.

-

Create a folder called

configfor the configuration filesmkdir -p src/config -

Create configs for the each environment:

-

Dev:

ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/src/config/development.json{ "text": "dev config" } -

Stage:

ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/src/config/stage.json{ "text": "stage config" } -

Production:

ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/src/config/production.json{ "text": "production config" }

-

-

Update the lambda function to load the config file (of the current environment) and return the

textvalue in the response:// examples/ch6/tofu/live/lambda-sample/src/index.js const config = require(`./config/${process.env.NODE_ENV}.json`); // (1) exports.handler = (event, context, callback) => { callback(null, { statusCode: 200, body: `Hello from ${config.text}!` }); // (2) };- (1): Load the config file (of the current environment).

- (2): Response with the

textvalue from the config file.

-

Deploy the new configurations (of each environment) in each workspace (AWS account):

-

Switch to an OpenTofu workspace

tofu workspace select development -

Run the OpenTofu commands with the corresponding AWS profile

tofu apply -var aws_profile=dev-admin

-

-

Repeat for the other environments.

[!TIP] To see all OpenTofu workspaces, use the

tofu workspace listcommand.$ tofu workspace list default development staging * production

Close your child accounts

caution

AWS doesn’t charge you extra for the number of the child accounts, but it DOES charge you for the resources running in those accounts.

- The more child accounts you have, the more chance you accidentally leave resources running.

- Be safe and close any child accounts that you don’t need.

-

Undeploy the infrastructure in each workspace (corresponding to an AWS account):

-

For

dev:tofu workspace select development tofu destroy -var aws_profile=dev-admin -

For

stage:tofu workspace select stage tofu destroy -var aws_profile=stage-admin -

For

prodtofu workspace select production tofu destroy -var aws_profile=prod-admin

-

-

Run

tofu-destroyon thechild-accountsmodule to closing the child accountscd ../child-accounts tofu destroy[!TIP] The destroy may fail if you create a new AWS with the OpenTofu module.

- It’s because an AWS Organization cannot be disabled until all of its child accounts are closed.

- Wait 90 days then re-run the

tofu destroy.

note

When you run close an AWS account:

-

Initially, AWS will suspense that account for 90 days,

This gives you a chance to recover anything you may have forgotten in those accounts before they are closed forever.

-

After 90 days, AWS will automatically close those accounts.

Get Your Hand Dirty: Manage Multiple AWS accounts

-

The child accounts after created will not have a password:

- Go through the root user password reset flow to “reset” the password.

- Then enable MFA for the root user of child account.

-

As a part of multi-account strategy,

- in additional to workload accounts (

dev,stage,prod) - AWS recommends several foundation accounts, e.g. log account, backup account…

Create your own aws-organizations module to set up all these foundational accounts.

- in additional to workload accounts (

-

Configure the

child-accountsmodule to store its state in an S3 backend (in the management account).

Get Your Hand Dirty: Managing multiple environments with OpenTofu and AWS

-

Using workspaces to manage multiple environments has some drawbacks, see this blog post to learn about

- these drawbacks

- alternative approaches for managing multiple environments, e.g. Terragrunt, Git branches.

-

Update the CI/CD configuration to work with multiple AWS accounts

You’ll need to

- create OIDC providers and IAM roles in each AWS account

- have the CI/CD configuration authenticate to the right account depending on the change

- configure, e.g.

- Run

tofu testin thedevelopmentaccount for changes on any branch - Run

plan,applyin thestagingaccount for any PR againstmain - Run

plan,applyin theproductionaccount whenever you push a Git tag of the formatrelease-xxx, e.g.release-v3.1.0.

- Run

Breaking Up Your Codebase

Why Break Up Your Codebase

Managing Complexity

Software development doesn’t happen in a chart, an IDE, or a design tool; it happens in your head.

(Practices of an Agile Developer)

-

Once a codebase gets big enough:

- no one can understand all of it

- if you need to deal with all of them at once:

- your pace of development will slow to a crawl

- the number of bugs will explode

-

According to Code Completion:

-

Bug density in software projects of various sizes

Project size (lines of code) Bug density (bugs per 1K lines of code) < 2K 0 – 25 2K – 6K 0 – 40 16K – 64K 0.5 – 50 64K – 512K 2 – 70 > 512K 4 – 100 -

Larger software projects have more bugs and a higher bug density

-

-

The author of Code Completion defines “managing complexity” as “the most important technical topic in software development.”

-

The basic principle to manage complexity is divide and conquer:

- So you can focus on one small part at a time, while being able to safely ignore the rest.

tip

One of the main goals of most software abstractions (object-oriented programming, functional programming, libraries, microservices…) is to break-up codebase into discrete pieces.

Each piece

- hide its implementation details (which are fairly complicated)

- expose some sort of interface (which is much simpler)

Isolating Products And Teams

As your company grows, different teams will have different development practices:

- How to design systems & architecture

- How to test & review code

- How often to deploy

- How much tolerance for bugs & outages

- …

If all teams work in a single, tightly-coupled codebase, a problem in any team/product can affect all the other teams/product.

e.g.

- You open a pull request, there is an failed automated test in some unrelated product. Should you be blocked from merging?

- You deploy new code that includes changes to 10 products, one of them has a bug. Should all 10 products be roll-backed?

- One team has a product in an industry where they can only deploy once per quarter. Should other teams also be slow?

By breaking up codebase, teams can

- work independently from each other

- teams are now interact via a well-defined interfaces, e.g. API of a library/web service

- have total ownership of their part of the product

tip

These well-defined interfaces allows everyone to

- benefit from the outputs of a team, e.g. the data return by they API

- without being subject about the inputs they need to make that possible

Handling Different Scaling Requirements

Some parts of your software have different scaling requirements than the other parts.

e.g.

- A part benefit from distributing workload across a large number of CPUs on many servers.

- Another part benefits from a large amount of memory on a single server

If everything is in one codebase and deployed together, handling these different scaling requirements can be difficult.

Using Different Programming Languages

Most companies start with a single programming language, but as you grow, you may end up using multiple programming languages:

- It may be a personal choice of a group of developers.

- The company may acquire another company that uses a different language.

- A different language is a better fit for different problems.

For every new language,

- you have a new app to deploy, configure, update…

- your codebase consists of multiple tools (for each languages)

How to Break Up Your Codebase

Breaking A Codebase Into Multiple Libraries

-

Most codebase are broken up into various abstractions - depending on the programming language - such as functions, interfaces, classes, modules…

-

If the codebase get big enough, it can be broken up even further into libraries.

A library

-

is a unit of code that can be developed independently from other units

-

has these properties:

-

A library exposes a well-defined API to the outside world

-

A well defined API is an an interface with well-defined inputs/outputs.

-

The code from the outside world can interact with the library only via this well-defined API.

-

-

A library implementation can be developed independently from the rest of the codebase

- The implementation - the internal - of the library are hidden from the outside world

- can be developed independently (from other units and the outside world)

- as long as the library still fulfills its promises (the interface)

- The implementation - the internal - of the library are hidden from the outside world

-

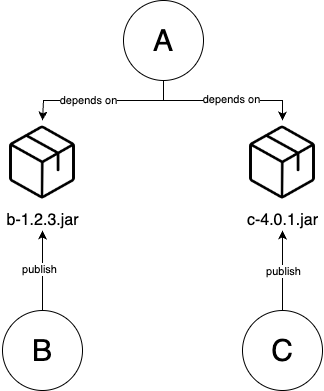

You can only depend on versioned artifact produced by a library, without directly depending on its source code

The exact type of artifact depends on a programming language, e.g.

- Java: a

.jarfile - Ruby: a Ruby Gem

- JavaScript: an npm package

As long as you use artifact dependencies, the underlying source code can live in anywhere:

- In a single repo, or

- In multiple repos (more common for library)

- Java: a

-

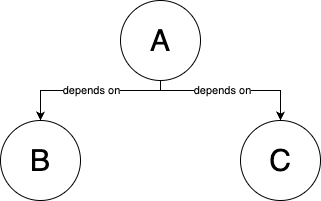

Example of a codebase before and after break up:

| Before break up | Break up | After break up |

|---|---|---|

|  | |

| A codebase with 3 parts: A, B, C | Turn B, C into libraries that publish artifacts , e.g. a.jar, b.jar files | Update A to depend on a specific version of these artifacts |

| Part A depends directly on source code of B and C | Part A depends on artifacts published by libraries B and C |

The advantage of breaking up codes base into libraries:

- Managing complexity

- Isolating teams/products

- The team that develope a library can work independently (and publish versioned artifact)

- The other teams that use that library

- instead of being affects immediately by any code changes (from the library)

- can explicitly choose to pull the new versioned artifact

important

Key takeaway #4 Breaking up your codebase into libraries allows developers to focus on one smaller part of the codebase at a time.

Best practices to break a codebase into multiple libraries

Sematic versioning

Semantic versioning (SemVer) : What? A set of rules for how to assign version numbers to your code : Why? Communicate (to users) if a new version of your library has backward incompatible changes13

With SemVer:

-

you use the version numbers of the format

MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, e.g.1.2.3 -

you increment these 3 parts of the version number as follows:

-

Increment the

MAJORversion when you make incompatible API changes. -

Increment the

MINORversion when you add functionality in a backward compatible manner. -

Increment the

PATCHversion when you make backward compatible bug fixes.

-

e.g. Your library is currently at version 1.2.3

- If you’ve made a backward incompatible change to the API -> The next release would be

2.0.0 - If you’ve add functionality that is backward compatible -> The next release would be

1.3.0 - If you’ve made a backward compatible bug fix -> The next release would be

1.2.4

note

With SemVer:

1.0.0is typically seen as the firstMAJORversion (first backward compatible release)0.x.yis typically used by new software to indicate incompatible change (breaking change) may be introduced anytime.

Automatic updates

Automatic updates : What? A way to keep your dependencies up to date : Why? When using a library, you can explicitly specify a version of library: : - This give you the control of when to use a new version. : - But it’s also easy to forget to update to a new version and stuck with an old version - which may have bugs or security vulnerabilities - for months, years. : - If you don’t update for a while, updating to the latest version can be difficult, especially if there any many breaking changes (since last update).

This is another place where, if it hurst, you need to do it more often:

-

You should set up an automatically process where

- dependencies are updated to source code

- the updates are rolled out to production (aka software patching 14)

-

This applies to all sort of dependencies - software you depend on - including:

- open source libraries

- internal libraries

- OS your software runs on

- software from cloud providers (AWS, GCP, Azure…)

-

You can setup the automation process

-

to run:

- on a schedule, e.g. weekly

- in response to new versions being released

-

using tools: DependaBot, Renovate, Snyk, Patcher

These tools will

- detect dependencies in your code

- open pull requests to update the code to new versions

You only need to:

- check that these pull requests pass your test suite

- merge the pull requests

- (let the code deploy automatically)

-

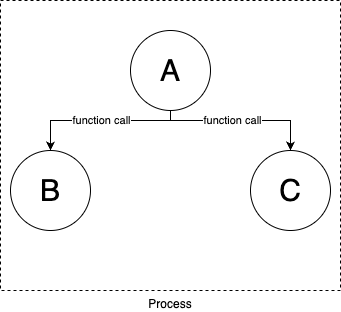

Breaking A Codebase Into Multiple Services

What is a service

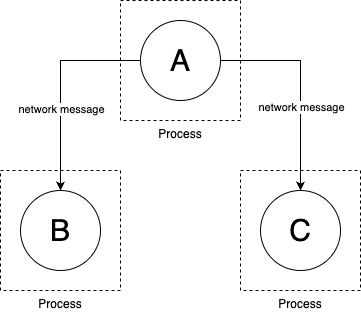

| Before | After |

|---|---|

|  |

| Codebase are broken up into source code, library/artifact dependencies | Codebase are broken up into separate services |

| All the parts of the codebase | Each part of the codebase (a service): |

| - run in a single process | - runs in a separate process (typically on a separate server) |

| - communicate via in-memory function calls | - communicates by sending messages over the network |

A service has all properties of a library:

- It exposes a well-defined API to the outside world

- Its implementation can be developed independently of the rest of the codebase

- It can be deployed independently of the rest of the codebase

with an additional property:

- You can only talk to a service via messages over the network (via messages)

How to break up codebase into services

There are many approaches to build services:

| Approach to build services | How | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Service-oriented architecture (SOA) | Build large services that handle all the logic for an entire business/product within a company | API exposed by companies - aka Web 2.0 e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Google Map… |

| Microservices | Build smaller, more fine-grain services that handle one domain within a company | - One service to handle user profiles - One service to handle search - One service to do fraud detection |

| Event-driven architecture | Instead of interacting synchronously15, services interact asynchronously16 |

Why breaking a codebase into services

The advantages of breaking a codebase into services:

-

Isolating teams

Each service is usually owned by a different team.

-

Using multiple programming languages

- For each service, you can pick the programming language that are best fit for a certain problem/domain.

- It’s also easier to integrate code bases from acquisitions & other companies (without rewrite all the code).

-

Scaling services independently

e.g. You can:

- Scale one service horizontally (across multiple servers as CPU load goes up)

- Scale another service vertically (on a single server with large amount of RAM)

important

Key takeaway #5 Breaking up your codebase into services allows different teams to own, develop, and scale each part independently.

Challenges with Breaking Up Your Codebase

caution

In recent years, it became trendy to break up a codebase, especially into microservices, almost to the extent where “monolith” became a dirty word.

- At a certain scale, moving into services is inevitable.

- But until you get to that scale, a monolith is a good thing

Challenges With Backward Compatibility

note

Libraries and services consist of 2 parts:

- The public API.

- The internal implementation detail.

When breaking up your codebase:

- the internal implementation detail can be changed much more quickly 👈 each team can have full control of it

- but the public API is much more difficult to be changed 👈 any breaking changes can cause a lot of troubles for the users

e.g. You need to change a function’s name from foo to bar

B is part of your codebase | B is a library | B is a service |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Discuss with your team if you really need a breaking change | 1. Discuss with your team if you really need a breaking change | |

1. In B, rename foo to bar | 2. In B, rename foo to bar | 2. Add new version of your API and/or new endpoint that has bar |

- Don’t remove foo yet | ||

| 3. Create a new release of B: | 3. Deploy the new version of your service that has both foo and bar | |

- Update the MAJOR version number | 4. Notify all users | |

| - Add release notes with migration instructions | - Update your docs to indicate there is a new bar endpoint and that foo is deprecated | |

| 4. Other teams choose when to update the new version: | 5. You wait for every team to switch from foo to bar in their code and to deploy a new version of their service. | |

| - It’s a breaking change, they’ll wait longer before update. | ||

| - They decide to upgrade | ||

2. Find all usages of foo (in the same codebase) and rename to bar. | - They all usages of foo and rename to bar | |

- You might even monitor the access logs of B to see if the foo endpoint is still being used, identify the teams responsible, and bargain with them to switch to bar. | ||

| - Depending on the company and competing priorities, this could take weeks or months. | ||

6. At some point, if usage of foo goes to zero, you can finally remove it from your code, and deploy a new version of your service. | ||

| - Sometimes, especially with public APIs, you might have to keep the old foo endpoint forever. | ||

| 3. Done. | 5. Done | 7. Done |

tip

You may spend a lot of time over your public API design.

- But you’ll never get it exactly right

- You’ll always have to evolve it overtime.

Public API maintenance is always a cost of breaking up your codebase.

Challenges With Global Changes

When breaking up your codebase, any global changes - changes that require updating multiple libraries/services - become considerably harder.

e.g.

-

LinkedIn stared with a single monolithic application, written in Java, called Leo.

-

Leo became bottleneck to scaling (more developers, more traffic).

-

Leo is broken into libraries/services.

- Each team was able to iterate on features within their libraries/services much faster.

- But there are also global changes.

-

Almost every single service relied on some security utilities in a library called

util-security.jar. -

When a vulnerability in that library was found, rolling out new version to all services took an enormous effort:

- A few developers is assigned to lead the effort

- They dig through dozens of services (in different repos) to find all services that depends on

util-security.jar - They update each of those services to new version, which can:

- be a simple version number bump.

- require a number of changes throughout the service’s code base to upgrade through many breaking changes.

- They open pull request, wait for code reviews (from many teams) and prodding each team.

- The code is merged; then they have to bargain with each team to deploy their service.

- Some of the deployments have bugs or cause outages, which requires: rolling back, fixing issues, re-deploying.

important

Key takeaway #6 The trade-off you make when you split up a codebase is that you are optimizing for being able to make changes much faster within each part of the codebase, but this comes at the cost of it taking much longer to make changes across the entire codebase.

Challenges With Where To Split The Code

If you split the codebase correctly:

- Changes done by each team are within their own part of the codebase, which

- allows each team to go much faster.

If you split the codebase wrong,

- Most changes are global changes, which

- makes you go much slower.

caution

When to break up a codebase?

Don’t split the codebase too early

- It’s easy to identify the “seam” in a codebase that has been around for a long time.

- It’s hard to predict/guess in a totally new codebase.

Some hints for where the codebase could be split:

-

Files that change together

e.g.

- Every time you make a change of type

X, you update a group of filesA - Every time you make a change of type

Y, you update a group of filesB

Then

AandBare good candidates to be broken out into separate libraries/services. - Every time you make a change of type

-

Files that teams focus on

e.g.

- 90% of the change by team

Zare in a group of filesC - 90% of the change by team

Ware in a group of filesD

Then

CandDare good candidates to be broken out into separate libraries/services. - 90% of the change by team

-

Parts that could be open sourced our outsourced

If you could envision a part of your codebase that would be:

- a successful, standalone open source project

- exposed as as successful, standalone APIs

then that part is a good candidate to be broken into a library/service.

-

Performance bottlenecks

e.g.

- If 90% of the time it takes to serve a request is spent in part

Eof your code,- and it’s most limited by RAM then part E is a good candidate to be broken out in to a service (to be scaled vertically).

- If 90% of the time it takes to serve a request is spent in part

caution

Don’t try to predict any of these hints! Especially for performance bottlenecks17.

The only way to know where to split the code is:

- Start with a monolith18

- Grow it as far as you can

- Only when you can scale it any further, then break it up into smaller pieces

Challenges With Testing And Integration

caution

Breaking up a codebase into libraries/services is the opposite of continuous integration.

When you’ve break up your codebase, you choose to

- allow teams to work more independently from each other

- in the cost of doing late integration (instead of continuous integration)

So only break up those parts that are truly decoupled, independent from other parts.

warning

If you split up the parts are tightly coupled, there would be many problems.

Teams will try to

- work independently, and not doing much testing and integration with other teams…

- or integrate all the time and make a lot of global changes…

important

Key takeaway #7 Breaking up a codebase into multiple parts means you are choosing to do late integration instead of continuous integration between those parts, so only do it when those parts are truly independent.

Dependency Hell

If you break up your codebase into libraries, you may face dependency hell:

-

Too many dependencies

If you depends on dozens of libraries

- each library depends of dozens more libraries

- each library depends of dozens more libraries

- …

- each library depends of dozens more libraries

Then only to download all your dependencies can take up a lot of time, disk space & bandwidth.

- each library depends of dozens more libraries

-

Long dependency chains

e.g.

- Library

Adepends onBBdepends onC- …

Xdepends onYYdepends onZ

- …

- If you need to make an important security patch to

Z, how to roll it out toA?- Update

Z, release new version forZ- Update

Y, release new version forY- …

- Update

B, release new version forB- Update

A, release new version forA

- Update

- Update

- …

- Update

- Update

- Library

-

Diamond dependencies

e.g.

Adepends onB,CBdepends onD(at1.0.0)Cdepends onD(at1.0.0)

- Then you upgrade

C:Bstill depends onDat1.0.0Cnow depends onDat2.0.0

You can’t have 2 conflicts versions of

Dat onces, now you’re stuck unless:BupgradeDto2.0.0- or you can’t upgrade

C

Operational Overhead

-

Each application need its own mechanism for software delivery: CI/CD pipeline, testing, deployment, monitoring, configuration…

-

If you split up a monolith into services that

- using the same programming language, each services needs its own CI/CD pipelines… for delivery. In other words, there will be many duplications, which means more operation overhead.

- using different programming languages, each services needs its own CI/CD pipelines that are completely different, which means even more operational overhead.

Dependency Overhead

With $N$ services,

- you have $N$ services to deploy & manage.

- but there are also the interactions between those services, which grows at a rate of $N^2$.

e.g.

-

Service

Adepends on serviceB- Add endpoint

footoB(Bat versionv2) - Update the code in

Ato make calls tofooendpoint (Aat versionv2)

- Add endpoint

-

When to deploy

Av2 andBv2?- If

Av2 is deployed beforeBv2,Amay try to callfooendpoint, which cause a failure (becauseBv1 doesn’t have thefooendpoint yet) BMUST be deployed beforeA👈 This is called deployment ordering

- If

-

Bitself may depend on servicesCandDand so on…- Now you need to have a deployment graph to ensure the right services are deployed in the right order.

-

If service

Chas a bug, you need to:- rollback

C - rollback the services that depends on

Cand so on… - things become so much messy

- rollback

tip

Deployment ordering can be avoided if

-

the services are written in a way that they can be deployed/rolled back in any order & at any time.

- one way to do that is use feature flags.

e.g.

- Service

Adepends on serviceB- Add endpoint

footoB(Bat versionv2)

- Add endpoint

- Update the code in

Ato make calls tofooendpoint (Aat versionv2)- Wrap that code in an if-statement which is off by default 👈 The new functionality is wrapped in a feature flag.

- Now

AandBcan be deployed in at any order & at any time- When you’re sure both the new versions of

AandBare deployed, then you turn the feature toggle on.- Everything should start working.

- If there is any issue with

AorB(or any of their dependencies), you turn the feature toggle off, then roll back the services.

- When you’re sure both the new versions of

Debugging Overhead

-

If you have dozens of services, and users report a bug:

- You have to investigate to figure out which service is at fault.

-

To track down a bug across dozens of services can be a nightmare:

Monolith Services Logs In a single place/format In different places/formats How to reproduce bug? Run a single app locally Run dozens of services locally How to debug? Hook a debugger (to a single process) and go through the code step-by-step Use all sorts of tracing tools to identify dozens of processes (that processing a single request) How long to debug? A bug that take an hour to figure out The same bug could takes weeks to track down -

Even if you you figure out the service at fault, there are still other problems:

- Each team will immediately blame other teams, because no one want to take ownership the bug.

- Your services are communicate over the network, there are a lot of new, complicated failure conditions that are tricky to debug.

Infrastructure Overhead

When you have multiple services:

- In additional to deploy the services themselves

- You need to deploy a lot of extra infrastructure to support the services.

- The more services you have, the more infrastructure you need to support them.

e.g. To deploy 12 services, you may also need to deploy:

- an orchestration tool, e.g. Kubernetes

- a service mesh tool, e.g. Istio 👈 To help services communicate more securely

- an event bus, e.g. Kafka

- a distributed tracing tool, e.g. Jaeger 👈 To help with debugging & monitoring

- (You also need to integrate a tracing library - e.g. OpenTracing - to all services)

Performance Overhead

When you breaking your codebase into services:

-

the performance may be improved 👈 you can handle different scaling requirements by horizontally or vertically scaling some parts of your software.

-

or the performance may also be worse.

This is due to:

-

Networking overhead

Operation How much? Where? Time in $μs$ Notes Read (Random) from DRAM - main memory $0.1$ TCP packet round trip 1.5 KB within same data-center $500$ $0.5 ms$ TCP packet round trip 1.5 KB from California to New York

(1 continent)$40,000$ $40 ms$ TCP packet round trip 1.5 KB from California to Australia

(2 continents)$183,000$ $183 ms$ - For a monolith, different parts (of the codebase) run in a single process, and communicate via function calls (in the memory) 👈 A random read from main memory takes $0.1μs$

- For services, different parts (of the codebase) run in multiple processes, and communicate over network 👈 A roundtrip for a single TCP package in the same data center takes $500μs$

The mere act of moving a part of your code to a separate service makes it at least $5,000$ times slower to communicate.

-

Serialization19 overhead

When communicating over the network, the messages need to be processed, which means:

- packing, encoding (serialization)

- unpacking, decoding (de-serialization)

This includes:

- the format of the messages, e.g. JSON, XML, Protobuf…

- the format of the application layer, e.g. HTTP…

- the format for encryption, e.g. TLS

- the format for compression, e.g. Snappy 👈 Just compressing 1 KB with Snappy is 20 times slower than random read from main memory.

-

warning

When splitting a monolith into services, you often minimize this performance overhead by

- rewriting a lot of code for:

- concurrency

- caching

- batching

- de-dupling

But all of these things make your code a lot more complicated (compare to keeping everything in a monolith)

Distributed System Complexities

Splitting a monolith into services is a MAJOR shift: your single app is becoming a distributed system.

Dealing with distributed system is hard:

-

New failure modes

-

For a monolith, there are only several types of errors:

- a function return

- an expected error

- an unexpected error

- the whole process crash

- a function return

-

For services that run in separate processes that communicate over the network, there are a lot of possible errors:

The request may fail because

- the network

- is down

- is misconfigured, and send it to the wrong place

- the service

- is down

- takes too long to response

- starts responding but crash halfway through

- sends multiple responses

- sends response in wrong format

- …

You need to deal with all of these errors, which makes your code a lot more complicated.

- the network

-

-

I/O complexity

Sending a request over the network is a type of I/O (input/output).

-

Most types of I/O are extremely slower than operations on the CPU or in memory (See Reducing Latency section)

-

Most programming languages use special code to make these I/O operations faster, e.g.

- Use synchronous I/O that blocks the thread until the I/O completes (aka use a thread pool)

- Use asynchronous I/O that is non-blocking so code

- can keep executing while waiting for I/O,

- will be notified when that I/O completes

-

| Approach to handle I/O | synchronous I/O | asynchronous I/O |

|---|---|---|

| How? | Blocks the thread until the I/O completes 👈 aka use a thread pool | The I/O is non-blocking: |

| - Code can keep executing (while waiting for I/O) | ||

| - Code will be notified when the I/O completes | ||

| Pros | Code structure is the same | Avoid dealing with thread pool sizes |

| Cons | The thread pools need to be carefully sized: | Rewrite code to handle those notifications |

| - Too many threads: CPU spends all its time context switching between them 👈 thrashing | - By using mechanisms: callbacks, promises, actors… | |

| - Too few threads: code spends all time waiting 👉 decrease throughput |

-

Data storage complexity

When you have multiple services, each service typically manages its own, separate data store:

- allow each team to store & manage data to best fits their needs, and to work independently.

- with the cost of sacrificing the consistency of your data

warning

If you try to have data consistent you will end up with services that are tightly coupled and not resilient to outages.

In the distributed system world, you can have all both of data consistent and services that are highly decoupled.

important

Key takeaway #8 Splitting up a codebase into libraries and services has a considerable cost: you should only do it when the benefits outweigh those costs, which typically only happens at a larger scale.

Example: Deploy Microservices in Kubernetes

In this example, you’ll

- Convert the simple Node.js

sample-appinto 2 apps:

-

backend: represents a backend microservice that-

is responsible for data management (for some domain within your company)

- exposes the data via an API - e.g. JSON over HTTP - to other microservices (within your company and not directly to users)

-

-

frontend: represents a frontend microservice that-

is responsible for presentation

- gathering data from backends

- showing that data to users in some UI, e.g. HTML rendered in web browser

-

- Deploy these 2 apps into a Kubernetes cluster

Creating a backend sample app

-

Copy the Node.js

sample-appfrom chap 5cd examples cp -r ch5/sample-app ch6/sample-app-backend -

Copy the Kubernetes configuration for Deployment and Service from chap 3

cp ch3/kubernetes/sample-app-deployment.yml ch6/sample-app-backend/ cp ch3/kubernetes/sample-app-service.yml ch6/sample-app-backend/ -

Update the

sample-app-backendapp-

app.jsMake the

sample-appact like a backend:- by exposing a simple API that

- response to HTTP requests with JSON

app.get("/", (req, res) => { res.json({ text: "backend microservice" }); });[!TIP] Normally, a backend microservice would look up data in a database.

- by exposing a simple API that

-

package.json{ "name": "sample-app-backend", "version": "0.0.1", "description": "Backend app for 'Fundamentals of DevOps and Software Delivery'" } -

sample-app_deployment.ymlmetadata: name: sample-app-backend-deployment # (1) spec: replicas: 3 template: metadata: labels: app: sample-app-backend-pods # (2) spec: containers: - name: sample-app-backend # (3) image: sample-app-backend:0.0.1 # (4) ports: - containerPort: 8080 env: - name: NODE_ENV value: production selector: matchLabels: app: sample-app-backend-pods # (5) -

sample-app_service.ymlmetadata: name: sample-app-backend-service # (1) spec: type: ClusterIP # (2) selector: app: sample-app-backend-pods # (3) ports: - protocol: TCP port: 80 targetPort: 8080-

(2): Switch the service type from

LoadBalancertoClusterIP[!NOTE] A service of type

ClusterIPis only reachable from within the Kubernetes cluster.

-

-

Build and deploy the backend sample app

-

Build the Docker image (See Chap 4 - Example: Configure your Build Using NPM)

npm run dockerize -

Deploy the Docker image into a Kubernetes cluster

In this example, you’ll use a local Kubernetes cluster, that is a part of Docker Desktop.

-

Update the config to use context from Docker Desktop

kubectl config use-context docker-desktop -

Deploy the Deployment and Service

kubectl apply -f sample-app-deployment.yml kubectl apply -f sample-app-service.yml -

Verify the Service is deployed

kubectl get services

-

Creating a frontend sample app

-

Copy the Node.js

sample-appfrom chap 5cd examples cp -r ch5/sample-app ch6/sample-app-frontend -

Copy the Kubernetes configuration for Deployment and Service from chap 3

cp ch3/kubernetes/sample-app-deployment.yml ch6/sample-app-frontend/ cp ch3/kubernetes/sample-app-service.yml ch6/sample-app-frontend/ -

Update the

sample-app-frontendapp-

app.jsUpdate the frontend to make an HTTP request to the backend and render the response using HTML

const backendHost = "sample-app-backend-service"; // (1) app.get("/", async (req, res) => { const response = await fetch(`http://${backendHost}`); // (2) const responseBody = await response.json(); // (3) res.send(`<p>Hello from <b>${responseBody.text}</b>!</p>`); // (4) });-

(1): This is an example of service discovery in Kubernetes

[!NOTE] In Kubernetes, when you create a Service named

foo:- Kubernetes will creates a DNS entry for that Service

foo. - Then you can use

fooas a hostname (for that Service)- When you make a request to that hostname, e.g.

http://foo,- Kubernetes routes that request to the Service

foo

- Kubernetes routes that request to the Service

- When you make a request to that hostname, e.g.

- Kubernetes will creates a DNS entry for that Service

-

(2): Use

fetchfunction to make an HTTP request to the backend microservice. -

(3): Read the body of the response, and parse it as JSON.

-

(4): Send back HTML which includes the

textfrom the backend’s JSON response.[!WARNING] If you insert dynamic data into the template literal as in the example, you are opened to injection attacks.

- If an attacker include malicious code in that dynamic data

- you’d end up executing their malicious code.

So remember to sanitize all user input.

- If an attacker include malicious code in that dynamic data

-

-

package.json{ "name": "sample-app-frontend", "version": "0.0.1", "description": "Frontend app for 'Fundamentals of DevOps and Software Delivery'" } -

sample-app_deployment.ymlmetadata: name: sample-app-frontend-deployment # (1) spec: replicas: 3 template: metadata: labels: app: sample-app-frontend-pods # (2) spec: containers: - name: sample-app-frontend # (3) image: sample-app-frontend:0.0.1 # (4) ports: - containerPort: 8080 env: - name: NODE_ENV value: production selector: matchLabels: app: sample-app-frontend-pods # (5) -

sample-app_service.ymlmetadata: name: sample-app-frontend-loadbalancer # (1) spec: type: LoadBalancer # (2) selector: app: sample-app-frontend-pods # (3)- (2): Keep the service type as

LoadBalancerso the frontend service can be access from the outside world.

- (2): Keep the service type as

-

Build and deploy the frontend sample app

Repeat the steps in Build and deploy the backend sample app

tip

When you’re done testing, remember to run kubectl delete for each of the Deployment and Service objects to undeploy them from your local Kubernetes cluster.

Get Your Hands Dirty: Running Microservices

-

The frontend and backend both listen on port 8080.

- This works fine when running the apps in Docker containers,

- but if you wanted to test the apps without Docker (e.g., by running

npm startdirectly), the ports will clash.

Consider updating one of the apps to listen on a different port.

-

After all these updates, the automated tests in

app.test.jsfor both the frontend and backend are now failing.- Fix the test failures.

- Also, look into dependency injection and test doubles (AKA mocks) to find ways to test the frontend without having to run the backend.

-

Update the frontend app to handle errors:

e.g. The HTTP request to the backend could fail for any number of reasons, and right now, if it does, the app will simply crash.

- You should instead catch these errors and show users a reasonable error message.

-

Deploy these microservices into a remote Kubernetes cluster: e.g., the EKS cluster you ran in AWS in Part 3.

Conclusion

When your company grows, there will be scaling problems, which you can solve by

- breaking up your deployment into multiple environments

- breaking up your codebase into multiple libraries & services

Both approaches have pros and cons

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| Breaking up your deployment | 1. Isolate: | |

| - tests from production | ||

| - teams from each other | ||

| 2. If the environments are in different regions: | ||

| - Reduce latency | (at the cost of) having to rework your entire architecture | |

| - Increase resiliency | ||

| - Comply with local laws/regulations | ||

| 3. Configuration changes can cause outages (just as code changes) | ||

| Breaking up your codebase | 4. … into libraries: Developers can focus on a smaller part (of codebase) at a time | |

| 5. … into services: Different teams can own, developer & scale each part independently | ||

| 6. You can make change much faster within each part (library, service) | (at the cost of) it taking longer to make change across the entire codebase | |

| 7. You choose to do late integration (instead of continuous integration), so it only works for those parts are truly independent | ||

| 8. Has a considerable cost, so only do it when the benefits outweigh the cost, which only happens at a larger scale |

Latency is the amount of time it takes to send data between your servers and users’ devices.

GDPR (Global Data Protection Regulation)

HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)

HITRUST (Health Information Trust Alliance)

PCI DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard);

FedRAMP (Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program)

With active/standby mode, you have:

- One active database that serves live traffic.

- Other standby databases in other data centers that doesn’t serves live traffic.

When the active database went down, another standby database would become the new active database, and serve live traffic.

With active/active mode, you have multiple databases that serve live traffic at the same time.

TODO

A backward incompatible change (of a library) is a change that would require the users to

- update how they use the library in their code

- in order to make use of this new version (of the library)

e.g.

- you remove something (that was in the API before)

- you add something (that is now required)

Synchronously means each service

- messages each other

- wait for the responses.

Asynchronously means each service

- listens for events (messages) on an event bus

- processes those events

- creates new events by writing back to the event bus

For performance bottlenecks, you can never really predict without running a profiler against real code and real data.

Serialization is the process of

- translating a data structure or object state into a format that can be

- stored (e.g. files in secondary storage devices, data buffers in primary storage devices) or

- transmitted (e.g. data streams over computer networks) and

- reconstructed later (possibly in a different computer environment).